THE NEW ETHNOGRAPHIC INDUSTRY: AROUSAL OF CURIOSITY AND FONDNESS FOR NOVELTY

Most ethnographic shows in the part of Polish territory that had until 1918 belonged to the Russian Empire were organised in large urban centres connected by railway, such as Warsaw, Łódź and Lublin. Non-European performers could sometimes be seen in less populous towns (for example Kielce), yet our current state of research indicates that these were only visited by small troupes (consisting of as few as two members) managed by small businesses. These entrepreneurs also tried to profit from the type of entertainment popularised by the main players of the industry, who rarely included smaller towns in their itineraries through Central and Eastern Europe. Groups of non-European Others reached that part of the Russian Empire not only from the West, but also from the East, through the endeavours of businessmen from Russia. Warsaw hosted performances by African peoples and Native Americans, but also by visitors from the Far North, such as Samoyeds, Tartars and Kalmuks. Their shows were organised in various locations, most of which were owned by private proprietors. These owners tried to draw more spectators (and thus maximise their profits) by diversifying their offer: ethnographic shows were a very popular attraction with local audiences at the time. Thus far, studies do not indicate that shows organised in the region featured the so-called native villages, which were often seen at large industrial exhibitions and were the element that popularised the concept of ethnographic shows worldwide. This lack is all the more significant because including ethnographic villages in the program of the industrial exhibitions held not only in German or Habsburg lands but also within the Russian Empire served purposes other than simply entertaining the public. The surviving body of Polish-language press (conservative, women-oriented and satirical) published in Polish territories within the Russian Empire contains relatively many—for example as compared with Eastern European Galicia—descriptions of how the local public reacted to the performances of non-European people and to their presence in the given city, as well as to the specific kind of entertainment offered by the ethnographic shows. The urban elite often used the arrival of these ‘exotic’ visitors in the city to illustrate how they were “at the centre of the European world”. Thus, local newspapers frequently listed the European capitals in which the given troupe had previously performed. Shows staged by ‘exotic’ caravans invariably attracted much attention from the local public. The presence of ‘ethnographic actors’ made its mark on the imagination and creative output of local artists, including Pantaleon Szyndler, whom the Sinhalese shows inspired to paint a portrait of Pinkama (A Sinhalese Woman), and Seleman Maradano (The Sinhalese). The influence of non-Europeans was also apparent in the ways in which the local political and social reality was conceptualised. An entire host of famous Polish actresses have been cast as Władka, a young working-class woman from the well-known play Aszantka (The Ashanti Woman) written by Włodzimierz Perzyński in 1906.

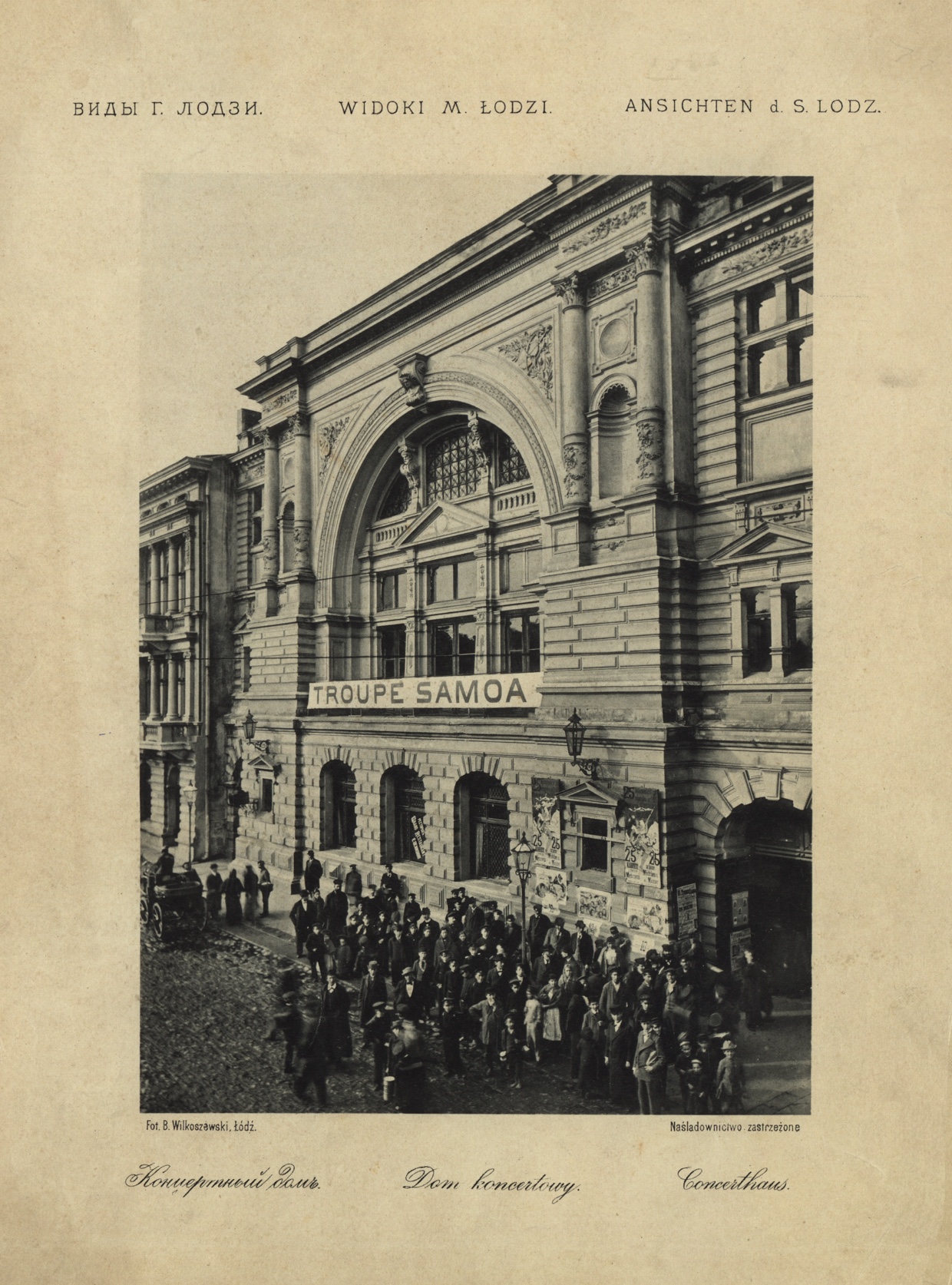

The front wall of the concert hall in Łódź, featuring a banner advertising performances by Samoans. Photographed by Bronisław Wilkoszewski, 1896. Source: The State Archive in Łódź, image collection, sign. PL_39_607_A-7_12.

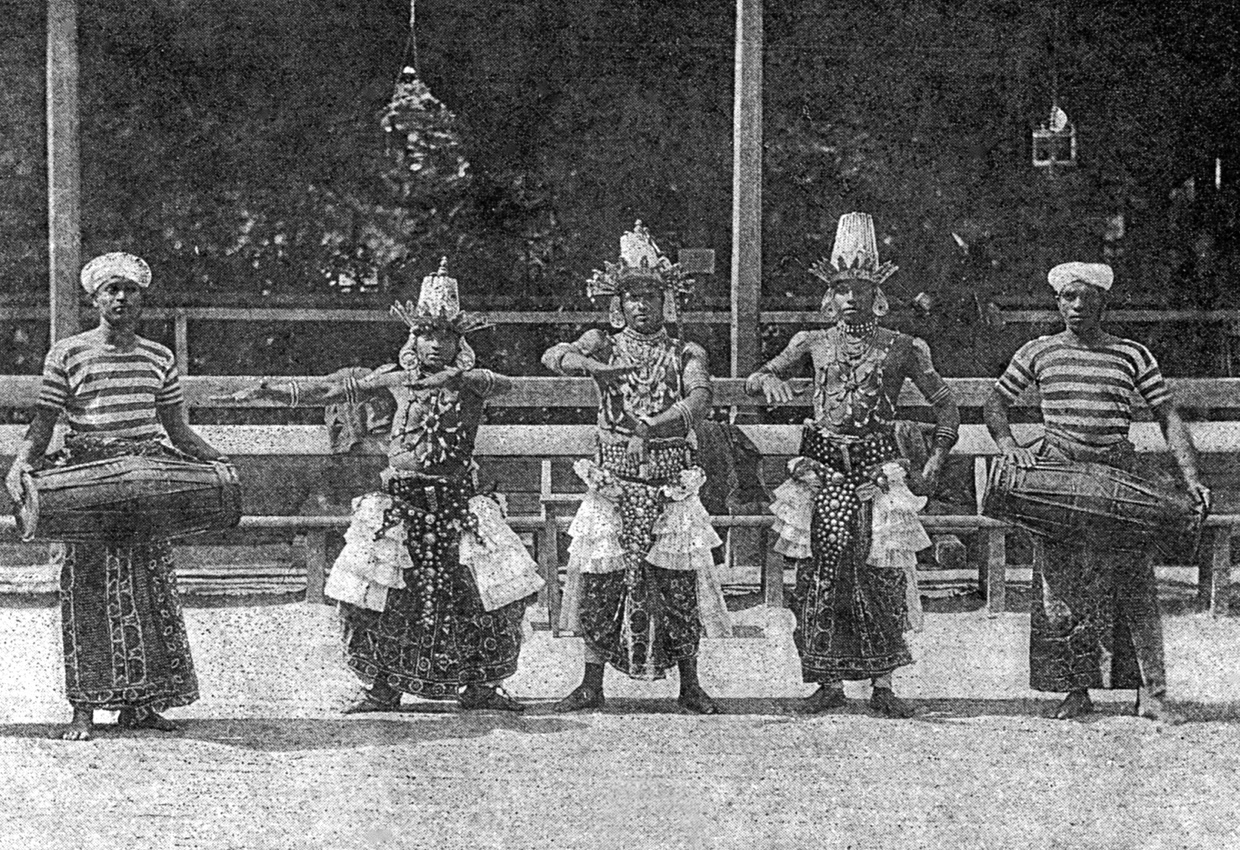

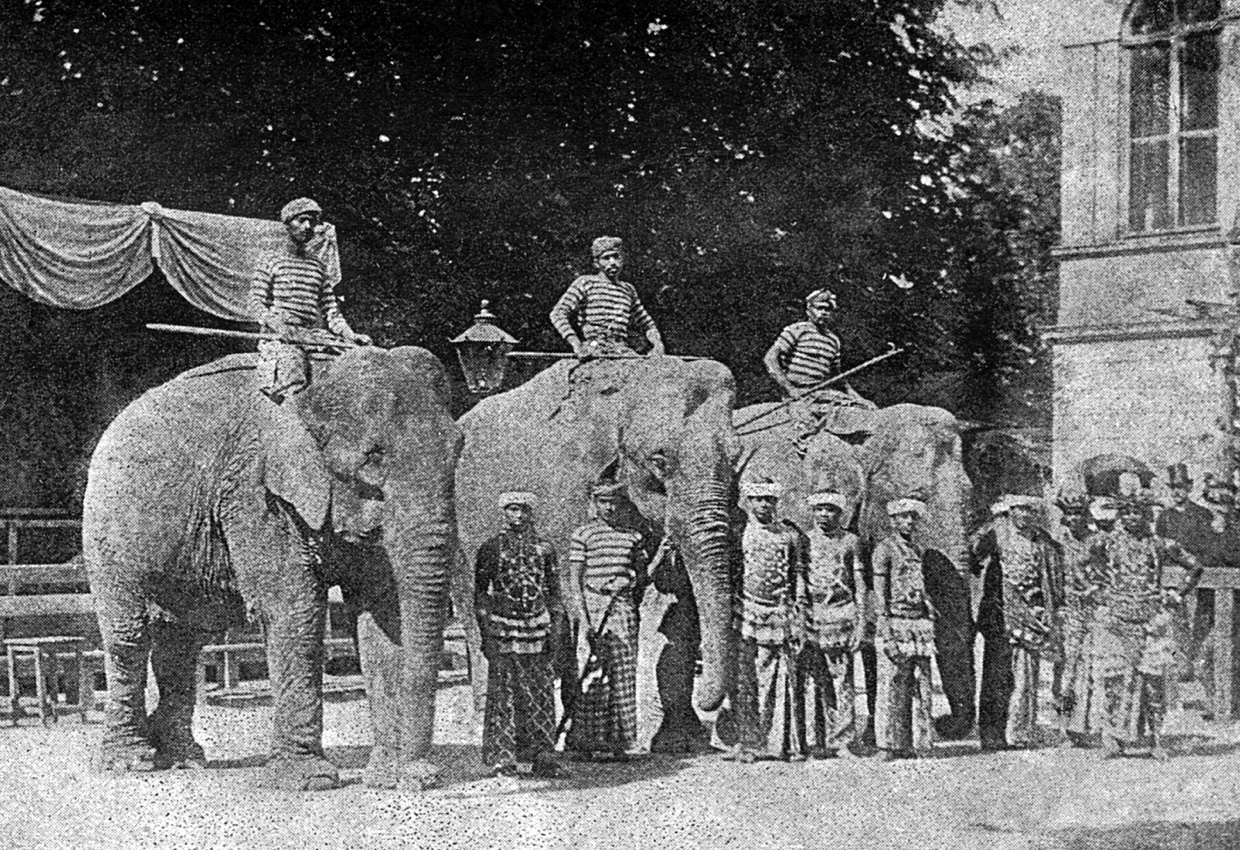

The Sinhalese performing at Warsaw zoo in 1888. Reproductions of photographs with the mark of the Rembrandt Photographic Atelier. Source: Tygodnik Ilustrowany, September 8, 1888.

“Singaleziana”. Source: Kolce, September 8, 1888.

In late August 1888 the impresario John George Hagenbeck arrived in Warsaw with a troupe of twenty-seven Sinhalese performers from Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka) accompanied by exotic animals, including five elephants. The Warsaw Zoological Garden, where the Sinhalese shows were staged, was then owned by Jan Maurycy Kamiński, to whom Hagenbeck had to promise the caravan would not perform elsewhere in the city. After more than two weeks, the troupe moved by train to Łódź, an industrial centre located along the route of the Warsaw–Vienna railway and something of a melting pot of cultures and nationalities at the time. Circus performances enjoyed much popularity in the city. As far as ethnographic shows featuring non-European Others are concerned, the most important organisers were the Sellin Theatre (later called the Variété Theatre) and the German public garden, featuring the first theatrical stage in Łódź, the Paradyz. It was that latter that in 1867 hosted performances by the black-skinned actor Ira Aldridge, who died of pneumonia soon after his arrival in Łódź and was buried in the Evangelical section of the Old Cemetery. The Sinhalese troupe also received an invitation to the Paradyz. Performances (seven in total) were held between September 12 and 19, 1888. The owner of the stage, to whom the local press referred as “Mr. Klukow” (most probably Michał Kunkel), covered the costs of their train journey to Łódź and back to Warsaw, which was over 200 roubles in total. He also paid for the food and lodgings for the troupe and their animals and offered Hagenbeck a salary of 400 roubles per day. The profits from the performances must have been considerable “given the widespread interest the visitors have sparked everywhere” (Dziennik Łódzki, September 16, 1888). Each day the Sinhalese shows at the Paradyz attracted a crowd of over two thousand spectators; on Sundays the number exceeded six thousand. The press in Łódź emphasised that the shows were a highly lucrative business, both for “Mr. Klukow” and for the caravan members, well compensated for their efforts by their impresario. Some performers earned the equivalent of 100 roubles per month, not counting the small tips (ca. 2 roubles per day) they collected from the audience. The greatest sums (even 10 roubles per day) were given to the two dwarves from Ceylon, Veruma and Cornelis Appo. Dwarf “freaks” were incorporated into the troupe in order to attract even more attention from curious spectators, thus increasing monetary profit. The financial aspects of the enterprise were often highlighted in the press, in Łódź as well as Warsaw. However, while journalists in Łódź were content with presenting calculations and specific estimates, the conservative titles in Warsaw criticised the performers’ voracious greed, which the local audience partially satisfied by spending thousands of roubles on “the brown amusements” (Biesiada Literacka, September 21, 1888).

Apart from the colour of their skin, the local media often commented on the sexual appeal of the Others of both genders—which was by no means tantamount to perceiving them as beautiful. In conservative and satirical press, the motif of sexual attractiveness of the Others was frequently connected with criticism of the behaviour displayed by female spectators. To exemplify, journalists reproached the “advances made by certain enthusiasts of modernity” towards a “half-savage Apollo” (Bluszcz, September 14, 1888; Dziennik Łódzki, September 19, 1888), who was a member of the Sinhalese caravan performing at the Warsaw Zoo in 1888. The 19-year-old Manik allegedly agitated female Varsavians so much that some of them followed him to Łódź. In practice, such passages appeared in the press not only to condemn affronts to moral principle and public decency, but also to draw the public’s attention to the dangers associated with the development of the women’s emancipation movement.

Impresario John Hood with the male members of the Dahomey caravan, photographed in Warsaw in July 1889. A pendant image showing Hood with the Dahomey women also existed. Both photographs were made by the Rembrandt Photographic Atelier. Source: Tygodnik Ilustrowany, July 13, 1889.

On June 19, 1889, the well-known impresario John Hood brought to Warsaw a caravan of nineteen Dahomeans. The local press offered sarcastic comments on the provenance of this “imitator of Hagenbeck”, who profited not only from Dahomey shows organised in various parts of the city, but also from selling African tools and ornaments to the ethnographic museum. Although the advertising campaign was centred around performances by the “valiant and cruel Amazons”, the caravan also included nine African men, one of whom was the 23-year-old Jam Benjamin Kolle. As with many other ‘ethnographic actors’, his story is a tragic one. Kolle died in the Hospital of the Infant Jesus early in July 1889 due to a gastrointestinal condition, and was buried at the cemetery of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Warsaw. The local public regarded his funeral as yet another attraction worth seeing. First, the coffin with the Dahomean’s remains was on display in the hospital chapel. Then a funerary procession made its way through Warsaw’s streets, followed not only by other members of the African troupe, but also by “a massive crowd of curious onlookers” (Kurier Warszawski, July 5, 1889). The Dahomeans resumed their tour soon after the funeral (on July 4, 1889), heading off to Lublin.

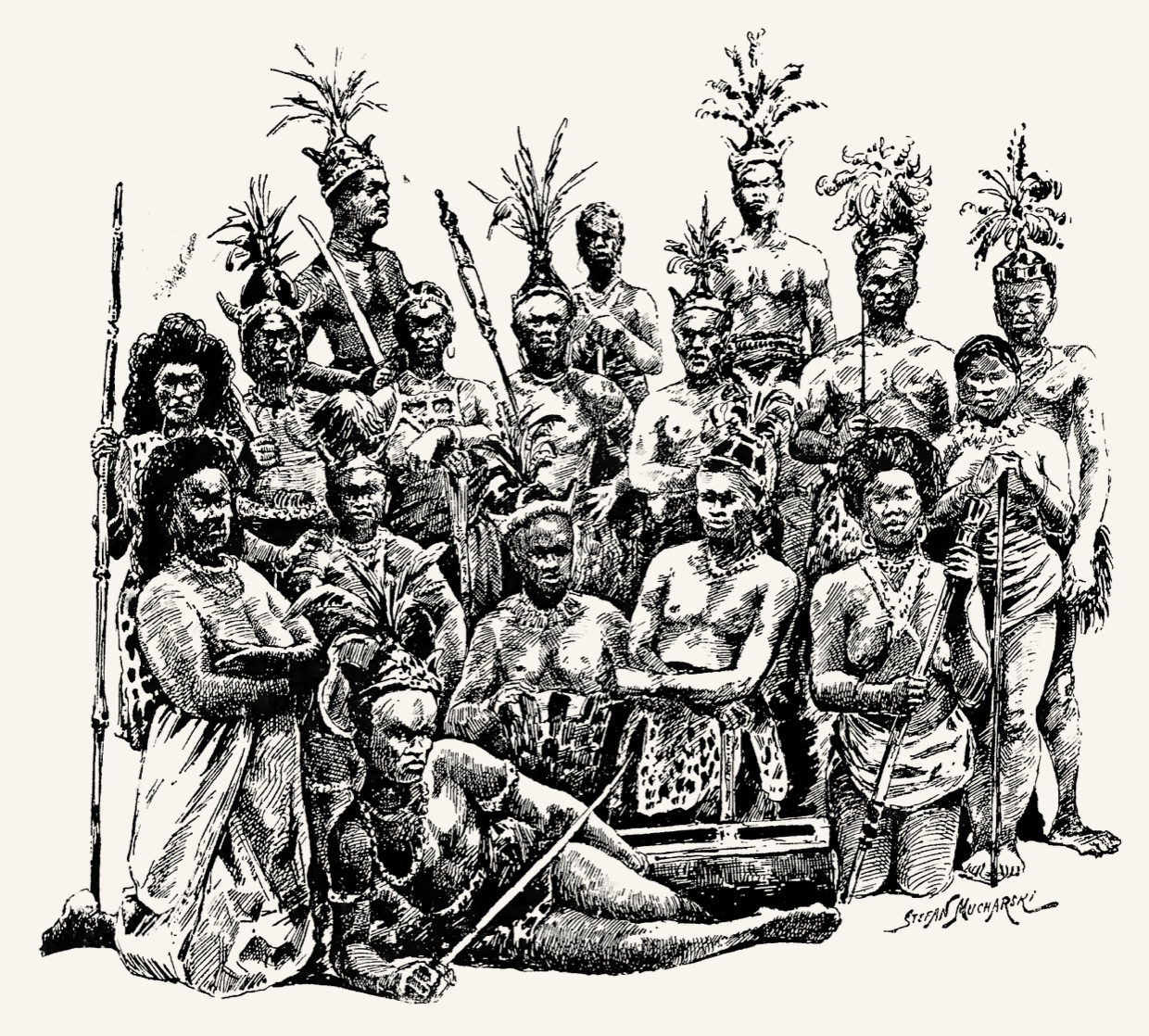

The Ashanti troupe in the Schumann Circus in Warsaw. Drawing by Stefan Mucharski. Source: Wędrowiec, January 26, 1888.

On January 17, 1888, the Schumann Circus in Warsaw hosted the first performance by the Ashanti from the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana). The troupe which, as the press said, arrived in Warsaw from Paris, comprised twenty people, including eight women and two children. “Since it would be unseemly to let them enter the arena in their… national attire” (Kurier Codzienny, January 18, 1888), the women were told to dress in leather costumes reaching down to their knees, and the men in broad loincloths. The ethnographic industry did not aim to show the audience any accurate representation of reality, but rather to replicate “images of recognisable exoticism”. At the same time, the degree of nudity on display was controlled in order not to offend the public’s moral sensibilities, yet in many cases the direct reason for interfering in the natives’ attire had to do with protecting them from the harsh climate. The Ashanti sparked so much interest in Warsaw that—according to the local press—watching their onstage performances was not enough to quell the curiosity of the audience. Varsavians would even pester members of the African troupe in their place of residence, which ultimately led to the number of social gatherings being limited by the group’s impresario.

Fake exhibitions were an integral part of the rapidly developing ethnographic industry. Not infrequently would show organisers deliberately falsify the identity of non-European people. In 1874, Warsaw’s daily press reported that reindeer shows were to be seen in Nowy Świat Street. The animal handlers were allegedly members of some community in the Far North, yet it soon became clear that the entire enterprise had been organised by Russians dressed up in Eskimo garb. The naivety of Varsavians was promptly ridiculed in the satirical press.

The Sinhalese shows and onlookers’ reactions. Excerpts from the press commenting on shows at Warsaw Zoo. Source: Tygodnik Ilustrowany, 1888.

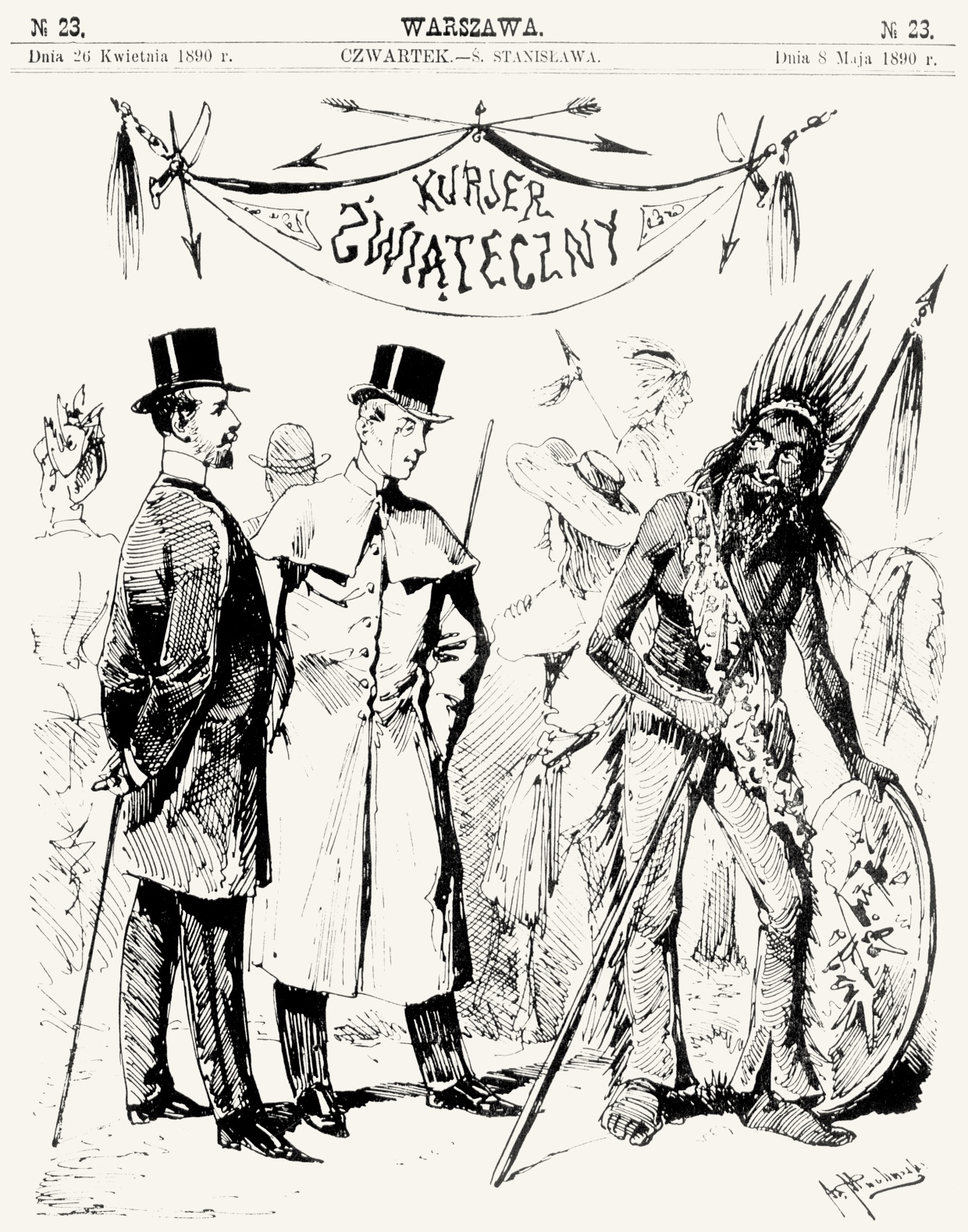

“The Warsaw Menagerie, most diligent in its efforts to amass material assets, has now, for the sake of mammon (which is the motor of all things in this century of ours), become the habitat of the Sinhalese, that is members of the Ceylon branch of the mighty Indian race. Over a dozen specimens of this tribe arrived in Warsaw to entertain the crowds in our zoological garden with their interesting visages. Their swarthy faces, eyes keen and burning, figures striking in shape and attire—all of this arouses the curiosity of the Varsovians, whose fondness for novelty (alas, only of the visual kind) will likely earn the Menagerie some income. The Sinhalese chat, laugh, dance, walk about with solemn countenances, and allow themselves to be watched in unique moments, in motion, in stillness, at rest while the Warsaw populace looks on, and admires, and gasps at who knows what, and comments on the things it sees with the vigour of deepest ignorance and with a truly childish credulity with regard to all gossip. And it must be said that gossip pertaining to these visitors from faraway Oceans spring up like mushrooms after the rain. Each detail of their dress provides fodder for talk, each motion stirs comments, and the entire phalanx of the brown newcomers inspires (in the Varsovians’ imagination) such a sense of dread that it seems certain that the crowd of onlookers would flee in all directions if one of them so much as lifted a fist. The Varsovians fear the ‘savages’, who are sure to be man-eaters. Indeed! All savages are man-eaters in the minds of mellow townies. The Sinhalese will stay at the Menagerie as long as it takes for their popularity and savagery to stop stirring human interest…”

![]()

Credits:

Dagnosław Demski, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences; Dominika Czarnecka, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences