THE GERMAN MODEL OF ADVERTISEMENTS VS. LOCAL FESTIVITY: CHANGING THE MEANING OF ETHNOGRAPHIC SHOWS

The poster advertises the arrival of Ostyaks and Zyryans at Moscow Zoo. The Ostyaks will give visitors rides in a sleigh pulled by dogs, the Zyryans in a sleigh pulled by reindeer. The entrance cost 32 kopecks for adults and 17 for children. Moscow Zoological Garden. Moscow: Levenson Printing House, 1899. Source: Collection of the Russian State Library, Moscow.

At the turn of the twentieth century Russia both exported and imported ethnographic exhibitions: Kalmyks, Tatars and Samoyeds were sent to Central and Western Europe while representatives of various peoples of Africa, Asia and America were brought to Russia. Exhibitions could be organised independently by Russian merchants of various ethnic and religious backgrounds, or jointly with foreign partners, mainly Germans. The increasing interest in ethnography and anthropology transformed the forms of the presence of unusual people in cities: for example, as early as the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, representatives of various peoples of the North were taking residents of St. Petersburg riding in sleighs with a reindeer team along the frozen Neva river and in streets. By the end of the nineteenth century, their performances were localised in zoos. These institutions saw their task as the dissemination of ethnographic knowledge, therefore, now cultural otherness was emphasised in the representatives of the peoples of the North. Other venues for ethnographic exhibitions were amusement gardens, panopticon-museums, theatres, circuses, ménages, department stores, industrial exhibitions and, before World War I, also cinemas. These places created a special context for the perception of unusual people: their strength, belligerence, bodily beauty, erotic attractiveness could be emphasised, as well as their savagery, ugliness, and disgusting appearance. Most of the exhibitions took place in St. Petersburg and Moscow, but they also took place in many other cities of European Russia and even in Siberia.

25 beauties from another part of the world, Samoa. Only a short time at the Schulze-Benkovskayae Museum and Panopticon. Saint-Petersburg: Zarkhin Printing House, 1896. Source: Collection of the Russian State Library, Moscow.

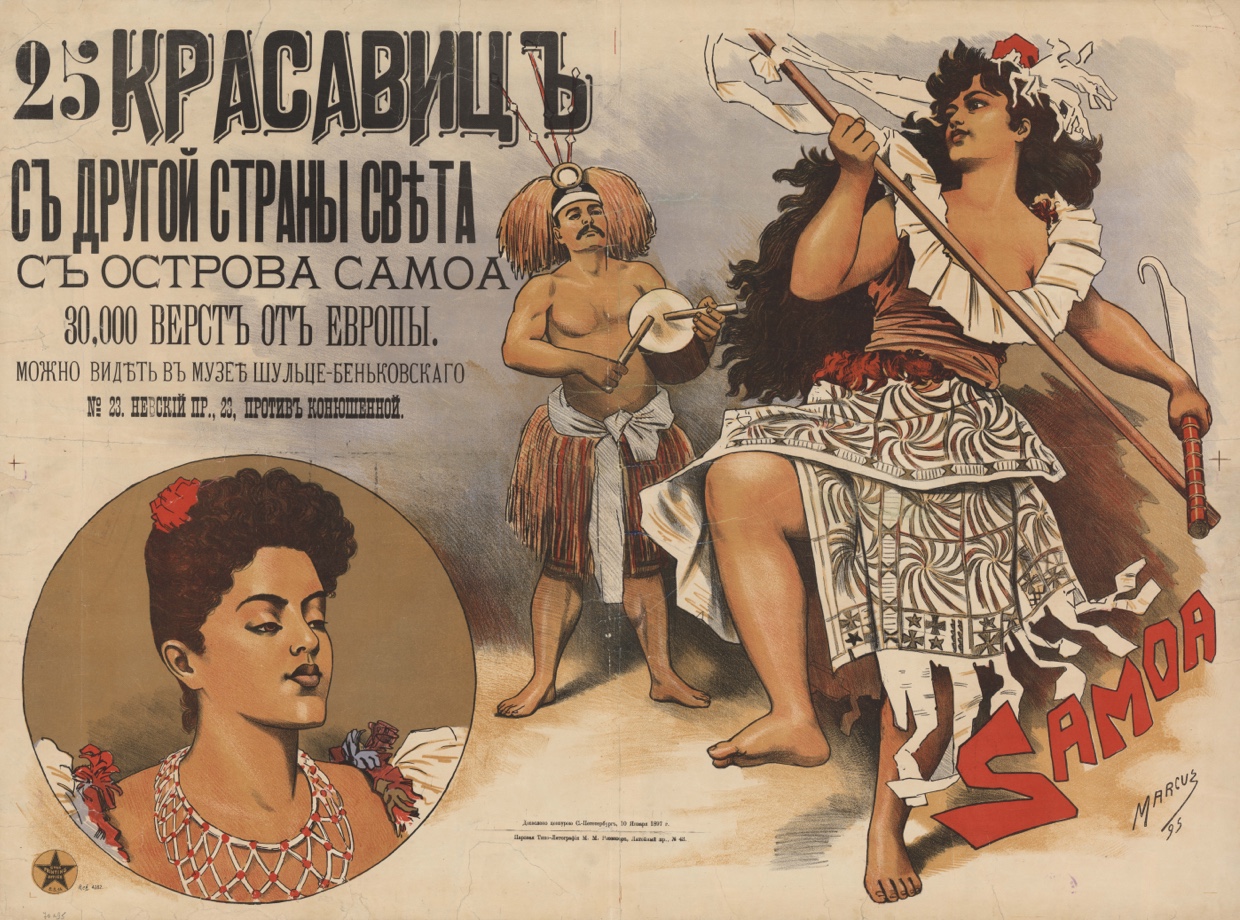

Marcus. 25 beauties from another part of the world, Samoa. Thirty-thousand versts from Europe. Can be seen at the Schulze-Benkovsky Museum. Saint-Petersburg: Rozenoer Printing House, 1897. Source: Collection of the Russian State Library, Moscow.

‘Samoan beauties’ were shown in the winter of 1896–97 at the Museum-Panopticon of M.A. Schulze-Benkovskaya in St. Petersburg. This museum, which had a dubious reputation, was founded in 1854 and toured various cities in Russia and abroad, for example Moscow, Rostov-on-Don, Kharkov, Kiev, Vilnius, Warsaw, Łódź, Riga, Berlin, London, etc. Along with the Samoan beauties, wax figures of foreign political celebrities could be seen in it: two Aztecs, also of wax; a live Hungarian boy “with a bird’s head”; a Russian peasant whose face was overgrown with hair; a picture of a woman buried alive, which was not recommended for people with weak nerves; a scene called “The Young Girl Abducted by a Gorilla”; images of genitals affected by various sexually transmitted diseases; a section on torture used by the Inquisition, etc. The advertisements initially mistakenly reported the arrival of Siamese beauties. A reporter for the French-language newspaper Journal de St. Petersbourg, who visited the exhibition, wrote that “these natives, who appear to the public in their national costumes, were once part of the caravan of Fritz Marquardt, chief of police in Apia, well known for his role in the fight against the kings Tamasese and Mataaf. Many admired the beauty of the Samoan women. Judging by the specimens that can be seen in the Schulze-Benkovskaya Museum, this is a fairly common beauty”. The journalist also noted that the ‘grotesque’ dances of the Samoans were reminiscent of the gypsies. Both posters for the exhibition reproduce German originals.

Dmitriev Мaxim. The Pavilion of the Far North during the All-Russian Industrial and Art Exhibition, Nizhny Novgorod, 1896. Source: Collection of the Аleksey Shusev State Museum of Architecture, Moscow.

At the All-Russian Industrial and Art Exhibition, held in Nizhny Novgorod in 1896, the Samoyeds were demonstrated in the pavilion of the Far North. It was a private pavilion erected by the builder of the Arkhangelsk Railway, Savva Mamontov, to advertise his project, which included big plans for the colonisation of the European North. Mamontov was also a philanthropist who supported new trends in art. The pavilion project was drawn up by the artist Konstantin Korovin, and the audience noted the deliberate rudeness of its forms. A pair of ‘wild’ Samoyeds, along with northern animals, were part of this artistic project. Korovin’s memoirs are full of racist jokes about the similarities between Samoyeds and seals. Due to the summer heat, many animals died, and the Samoyed Vasily also fell ill and was taken to hospital. Mamontov had to arrange ice under the pavilion, where, according to Korovin, the trained seal Vaska and the Samoyed Vasily slept nearby.

Leo Tolstoy visiting Moscow Zoo. Date uncertain: 1892 according to Tolstoy Museum, 1901 according to Maria Leskinen. Source: Collection of the Leo Tolstoy State Museum, Moscow.

Once an ethnographic exhibitions arrived in Russia its meaning could be changed. For example, advertisements for the Dahomey Amazons used German models producing a scene titles “Night in Dahomey”, which had obvious sexual connotations, while in Russia the Amazons were presented at the Easter holiday and any inappropriate hints were omitted. References to current politics did not matter much either. When the Amazons were shown in Germany, they were the very heroic warriors who had recently fought the French. In France, the same Amazons embodied new colonial achievements in West Africa. In this sense they could be demonstrated in Germany too, when correlated with the colony of Togo. Russia, however, was not involved in the colonial partition of Africa. More important for the Moscow audience was the fact that the Dahomeans had been shown a year earlier at the Paris World Exhibition of 1900. Attending their performances first at the Manege and then at the Zoo turned out to be a way to join the most important event in the cultural centre of Europe for those who did not have the opportunity to go there. Advertisements for the Amazons also mentioned that they came directly from Berlin, which added to their metropolitan chic. Getting into colonial entertainment turned out to be a way to overcome the feeling of one’s own provinciality.

“Somali village” in Luna Park, St. Petersburg, 1912. Postcard. Source: Private Collection of Natalya Germanova, Rostov-on-Don.

All postcards issued for the arrival of the Somalis reproduce earlier German originals, on this one you can see the German inscription “Stamm Essa”. The postcard was sent to Odessa with “heartfelt wishes” for the recipient’s name day.

Chikin A. Saint Petersburg Zoological Garden. Saint Petersburg: Golike Printing House, 1899. Source: Collection of the Russian State Library, Moscow.

Participants in the ethnographic exhibitions brought to Russia did not always have warm clothes or heated housing suitable for the climate. According to newspaper reports, in April–May 1901 participants in the Dahomey Amazon caravan at Moscow Zoo lived in straw huts that were at sub-zero temperatures overnight.

In the winter of 1911, even the Samoyeds brought from the Far North suffered from the cold at Moscow Zoo. Their warm chum (tent) was transported separately and was delivered with a delay of several days. They had to temporarily live in a wooden gatehouse. Sometimes these stories ended tragically. The Russkoe slovo newspaper reported in May 1912 about the arrival of a group of Somalis:

Yesterday, a troupe from Riga arrived in St. Petersburg, which was taken out of Africa to participate in the Luna Park theatre opening in St. Petersburg. From the station, the troupe, representing some kind of gathering of naked people, went to the theatre on Officer Street. There are many women in the troupe, dragging small children on their backs in sacks. The whole troupe is dressed more than modestly: black belts that cover the hips and light sandals on the feet—that’s all. The arrival of the troupe at the theatre came as a complete surprise to the management; no one bothered to find a place for them. As a result, the entire troupe was driven into the garden and placed in a shed for decorations overnight. At night, the temperature in St. Petersburg dropped to 7 degrees below zero. The unfortunate Africans, huddled together in heaps, tried somehow to warm up. Some of them began to faint. The prudent entrepreneur, fearing that the Africans might flee, locked the shed. The shouts of the freezing ones were heard by the watchmen on duty at the gate. They informed the administration of the garden and then the police. When the shed was opened at 8 o’clock in the morning, they found one of the troupe—a 50-year-old man—dead. Today the whole troupe is housed in apartments.

Credits:

Evgeny Savitsky, Russian State University for Humanities in Moscow