WESTERN METROPOLITAN CULTURE AND EXHIBITING NON-EUROPEAN PEOPLE

The white, modern and progressive Western world of the nineteenth century developed a new mass-scale phenomenon the traces of which, in various forms, can still be observed within the logic of modern communication and spectacles. Ethnographic shows, which started to be staged more frequently in the 1850s, were a form of public, organised performances that involved putting on display living members of non-European ethnic groups, then commonly referred to as “races”. Although the earliest and the largest living human exhibitions were organised in Germany, England and France, performances of this kind could be seen almost everywhere in Europe, as well as in North and South America and Australia. They were at the peak of their popularity between the 1880s and the outbreak of the Great War. As an urban phenomenon, ethnographic shows were organised in various exhibitionary contexts, from world’s fairs, industrial or national exhibitions, through zoological gardens and other institutions invented in the nineteenth century, to circuses, private gardens and theatres. The shows attracted thousands of spectators, becoming an immensely popular form of entertainment for the masses. The undisputed leader of the so-called ethnographic industry was Carl Hagenbeck (1844–1913), a German entrepreneur whose initiatives soon found many imitators. Other known impresarios touring Europe with non-European performers included Viktor Bamberger, Robert A. Cunningham, Eduard Gehring, Ferdinand Gravier, Carl and Fritz Marquardt, Heinrich and Willy Möller, Emanuel Porfi, Jean-Alfred Vigé, John Wood/Hood, and William Frederick Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill. Due to the existence of various models of non-European human display, and many different contexts and functions that can be associated with them, this cultural phenomenon cannot be presented in a comprehensive manner by any one-dimensional interpretation.

Bedouin camp. Ethnographic show at the zoological garden in Vienna, July 24, 1900. The show takes place on a circular arena surrounded by a fence behind which the audience is gathered. In the middle is a group of Bedouins with horses, camels, and donkeys. On the right a row of Bedouin men standing in front of the guests of honour, seen on the main stand. Source: Collection Radauer.

Contemporary academic literature and popular culture has referred to living human exhibitions in many different ways, for example ethnic shows, ethnographic shows, Völkerschau, human ‘exotic’ displays, and human zoos. Although used frequently, the latter term appears relatively problematic and is often questioned by scholars. The problem lies not only in the fact that merely a fraction of such performances took place in zoological gardens. The term human zoo indicates a unilinear power relation and makes non-European peoples into victims, denying them any agency and screening out entangled history. While the power relations in ethnographic shows were not equal, but biased towards European impresarios, applying the term human zoo, which suggests that humans were collected like wild animals and put into zoos, to the entire cultural phenomenon is inaccurate and could lead to reproducing discourses of Western agency and non-Western powerlessness.

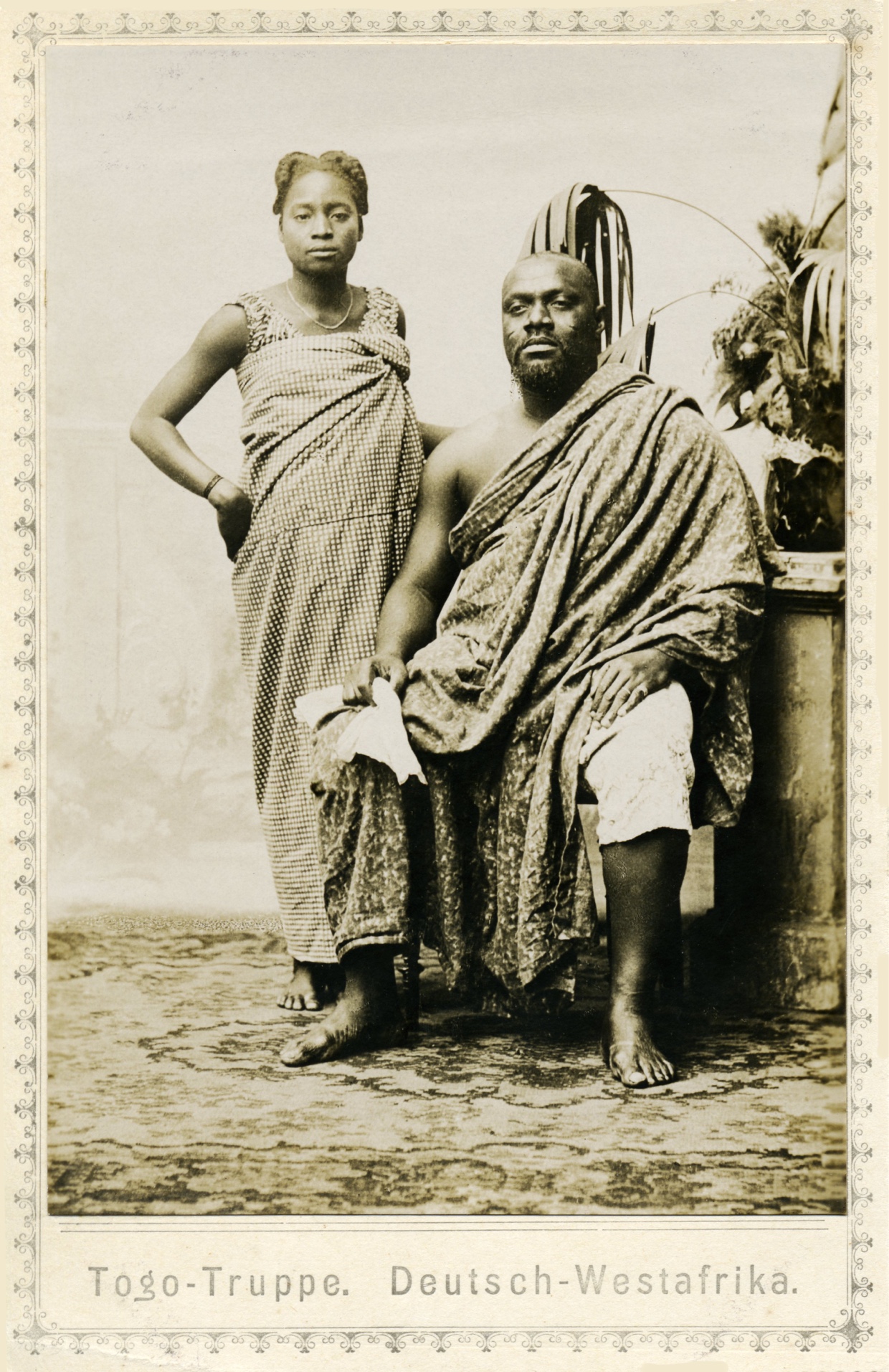

The Togo ethnographic troupe from German West Africa, 1901. Source: Collection Radauer.

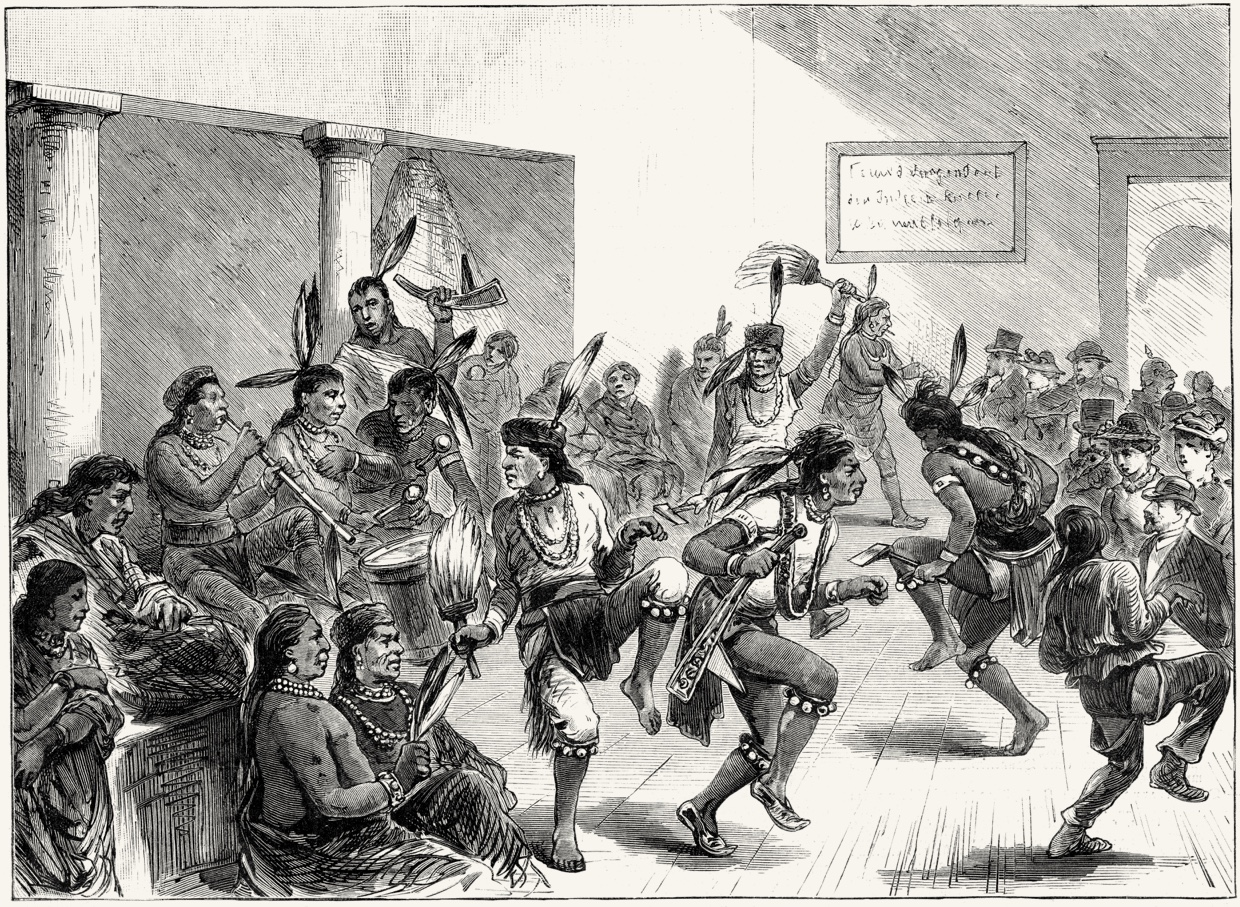

Sioux “Indians” in the Berlin Panopticon, 1884. Source: Illustrierte Zeitung, February 2, 1884. Collection Radauer.

Throughout the several decades of their development, ethnographic shows, intended to provide visual entertainment for the masses, underwent a fundamental transformation: from performances involving a dozen performers (at the most) to huge spectacles that could feature up to several hundred ‘ethnographic actors’ at once. Living human displays were organised in accordance with Western colonial logic, and designed for entertainment and the so-called popular education of European city dwellers. What mattered in ethnographic shows was not only showing ethnic or cultural differences, but demonstrating the validity of cultural and racial hierarchies developed in anthropology. These hierarchies invariably professed the inferiority of non-Europeans, then referred to as “savage” human types. These practices were used to present or suggest the existence of a gradation among humans in order to create distance between whites and non-whites, and reinforce the relations of superiority and subjugation.

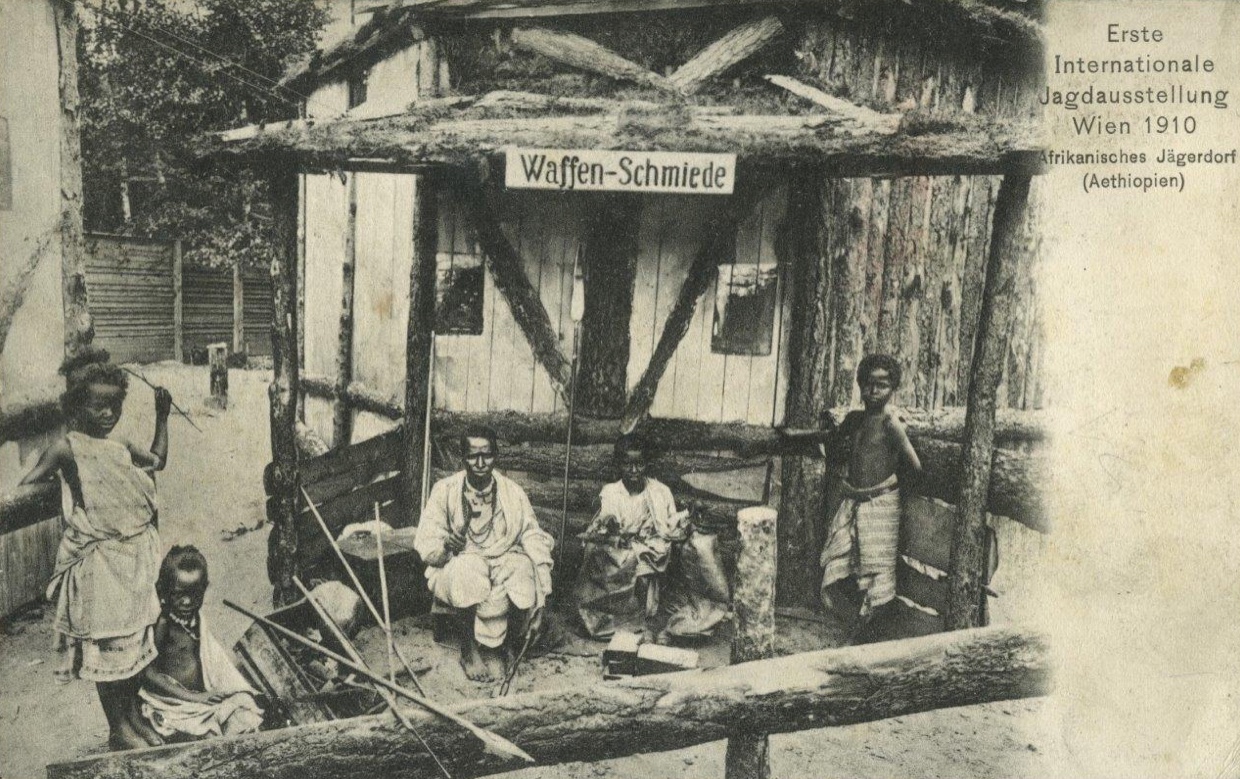

“Ethiopian village” organised at the Hunting Exhibition in Vienna, 1910. Source: Ethnographic Museum in Kraków.

Trends that had for several decades remained dominant in the organisation of ethnographic shows were initiated in the 1870s by Carl Hagenbeck. The change he suggested involved creating replicas of exotic places within European cities. As a cognitive concept of its time, this model was always somewhere between image and reality, but was intersubjective enough to be accepted as an objective truth. The visual model designed and developed by Hagenbeck was based on recreating popular geographic ‘illustrations’, known to European audiences from other sources such as books, newspapers, photographs. This meant transporting people, animals, plants and artefacts from remote corners of the world to Europe. This model, which became prevalent in the latter half of the nineteenth century, used ethnographic points of reference; real people and authentic artefacts were cut from their original context and pasted into a completely different one. Such presentation distorted original elements and strips of activity, warping them into something new, changing the message they conveyed. However, this physical dislocation and display of foreign people allowed ethnographic shows to satisfy the mass public’s need to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and in human terms.

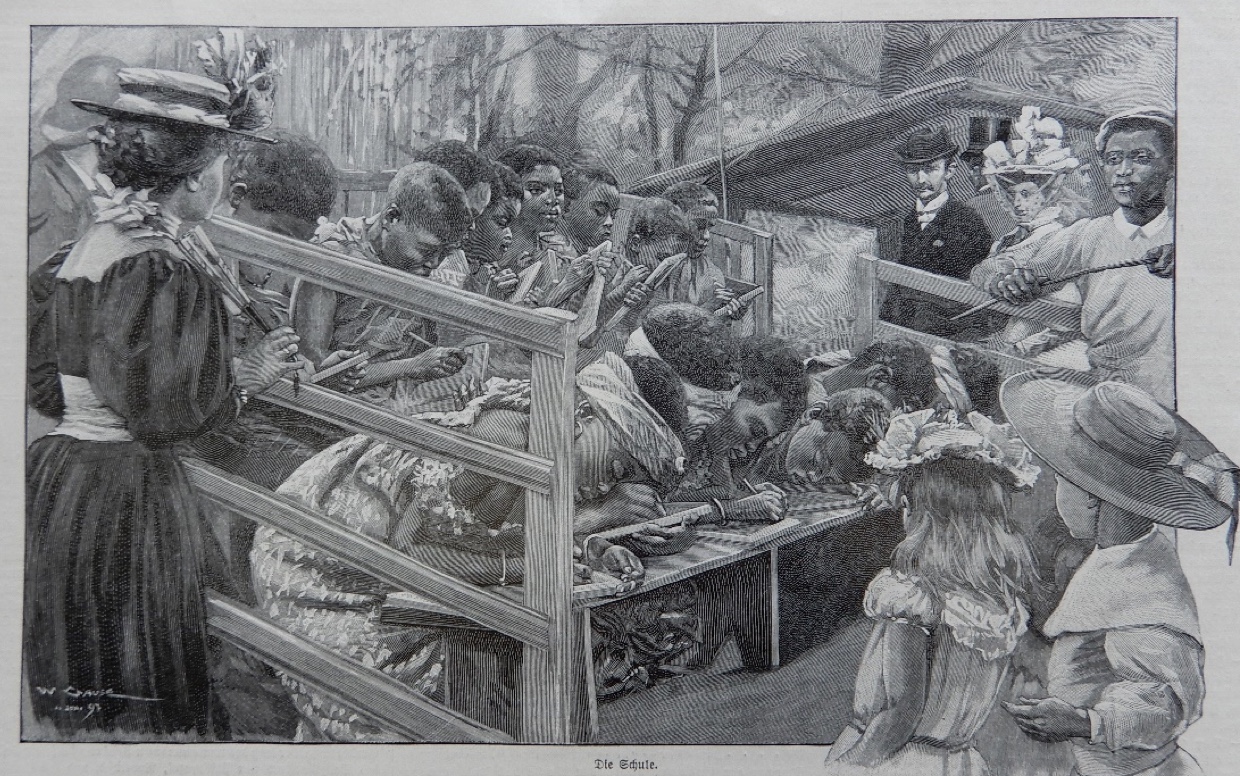

School for children in the “Ashanti village” organised in the Viennese zoological garden. Source: Illustrierte Zeitung, August 5, 1897.

The Hagenbeckian model of ethnographic performance (later copied by many others) was so successful mainly because it managed to combine visual and mass-cultural logic of difference and identification. Although spectators came to the show lured by the promise of seeing something exotic—most notably the living members of non-European communities—the scenes shown to them were surprisingly familiar. In practice, almost all aspects of the life of ‘exotic’ Others were on display: feeding animals, caring for children, dancing, singing, conducting wedding ceremonies. The shows offered European audiences a glance into the ‘real-life’ activities of non-European people, although the scenes they were seeing were easily recognisable. The domestic and the familiar was necessary for the visualisation of the exotic, and to make it more accessible to the general public. Thus, ethnographic shows invariably involved constant, lively interaction between sameness and difference, which made it possible for urban mass culture to assimilate the difference and make the exotic familiar.

Animal husbandry. Carl Hagenbeck’s Galla troupe, 1908. Source: Collection Radauer.

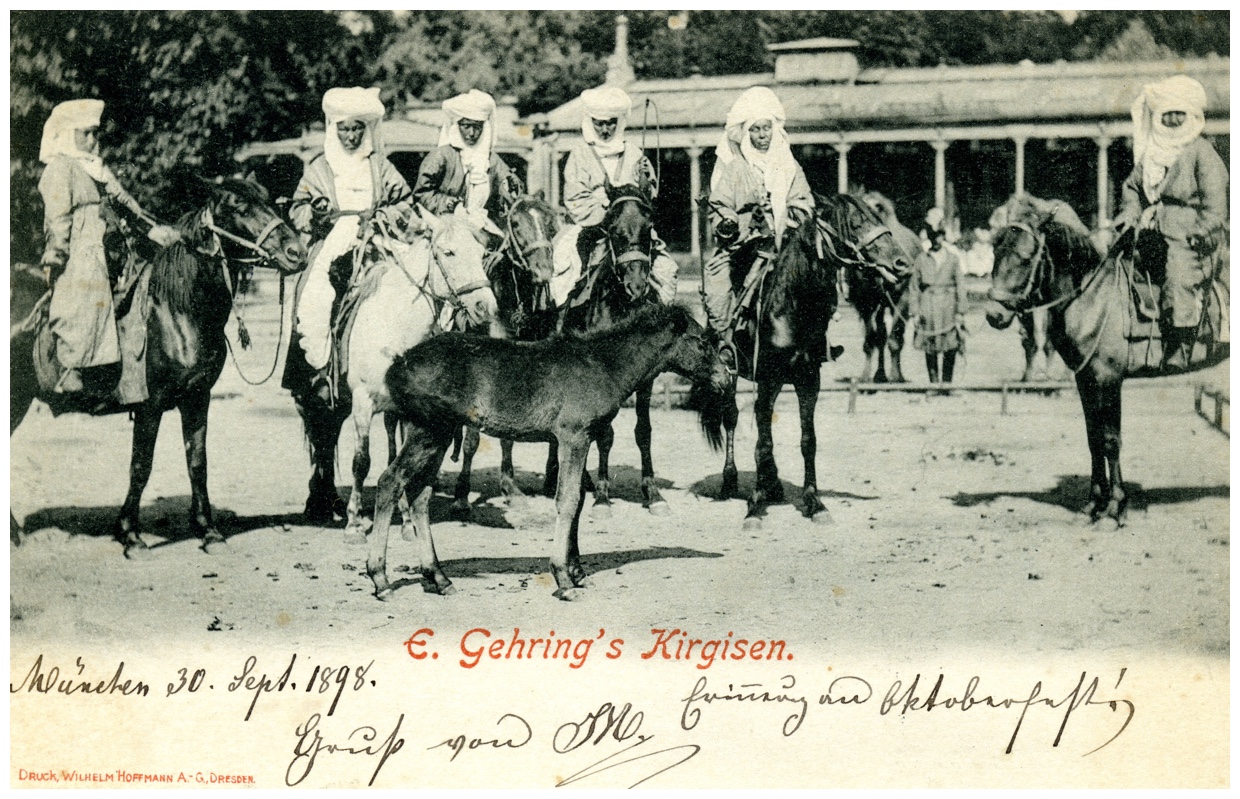

Eduard Gehring’s Kyrgyz women on horses. Munich, September 30, 1898. Source: Collection Radauer.

The growing success of ethnographic shows was directly related to the fascination with the ‘real’ and the ‘authentic’. In this context, the most important aspect of the performances was the physical presence of living members of non-European communities, which made such practices different from ethnographic exhibitions presented in museums. The dominant model of ethnographic shows established a very specific relationship between the present and the absent. Although the performances created a sense of unmediated encounter, the people put on display were not there to represent themselves as individuals, but rather to stand in for the absent community. The organisers of these shows denied that any representation was involved (especially at the initial stage in the evolution of the practice), trying to convince their audience that what they offered were ‘real’ scenes from the everyday lives of non-Europeans, a pure presence that had nothing to do with theatrical forms. This lack of overt performance was one of the elements that attracted large audiences, particularly at the early stage of the shows’ development. In later decades, performances took more elaborate and more theatrical forms, the elements becoming more staged, the performers becoming progressively more professional at ‘ethnographic acting’. The sense of authenticity was additionally enhanced by the creation of new, open exhibition spaces in which original scenery could be emulated in a more realistic fashion. The plants, animals and artefacts involved were deemed authentic if they were collected by field agents cooperating with the organisers of the shows, even more so if they were brought to Europe by the foreign performers.

![]()

Credits:

Dagnosław Demski, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences; Dominika Czarnecka, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences