BETWEEN ATTACHMENT TO TRADITION AND THE BREEZE OF APPROACHING MODERNITY

As the capital of Habsburg Galicia (1772–1918), Lviv was a very important link in the Galician urban network, comparable only to Kraków. Consequently, these were the cities in the province with the largest number of ethnographic shows organised in the latter half of the nineteenth and the early decades of the twentieth century. Urban centres such as Stanisławów, Przemyśl, Tarnów and Tarnopol played a less pronounced, albeit still important role. The Transversal Railway connected the empire’s ‘internal colony’ with other Austrian provinces: Austria had a considerable influence on the lives of Galicia’s inhabitants in the nineteenth century. One aspect of this influence was exhibition activity, in the broadest understanding of the term. Galicia followed the example of Vienna, where shows with non-European performers were highly popular. Many troupes that visited the cities and towns of the eastern reaches of the Habsburg Empire headed there directly from the capital. Thus far, research on ethnographic shows with non-European Others organised in Galicia found no evidence of performances involving the construction of ‘native villages’. This is surprising given the fact that non-European troupes (for example in East Prussia) often performed at all sorts of general, national and industrial exhibitions and other events that propagated the cult of progress. Many such initiatives were undertaken in Galicia—the 1894 General Regional Exhibition of Galicia in Lviv, to name just one—yet instead of performers from beyond Europe, the exhibitions in the region often featured Galicia’s own Others (for example Hutsuls). The attitude towards such ‘meetings with exoticism’ displayed by residents of each urban centre in the province ought not to be generalised, but rather considered in the context of specific towns and cities. Extant source material indicates that the audiences in Lviv showed more interest in ethnographic shows than was the case, for instance, in Kraków, the residents there being torn between their love of tradition and the allure of modernity. At the turn of the century, Lviv was a truly cosmopolitan metropolis, where ethnographic shows were regarded not only as entertainment, but also as a chance to participate in the European community of culture, including its educational aspect. Meanwhile, Kraków (the former capital of then defunct Poland), established in the Polish political and cultural identity as a symbol of Polish-ness and political freedom, had a sense of mission regarding the cultural life of the nation. At the same time, the city was falling further and further behind the on-going changes of modernity. Thus, ethnographic shows were not widely commented on in the local press. This does not mean that no breath of exoticism ever reached Kraków, or that its inhabitants did not have ‘exotic’ interests: the African collection of Stefan Szolc-Rogoziński, for instance, was on display three times (twice in 1884, and in 1886). As a form of entertainment that belonged in the field of popular science, ethnographic shows played a certain role in the process of creating the Krakovian model of Africa and Asia. As a form accentuating cultural as well as ‘racial’ boundaries, shows by non-European Others had at least indirect influence on the emergence of the canon of national culture.

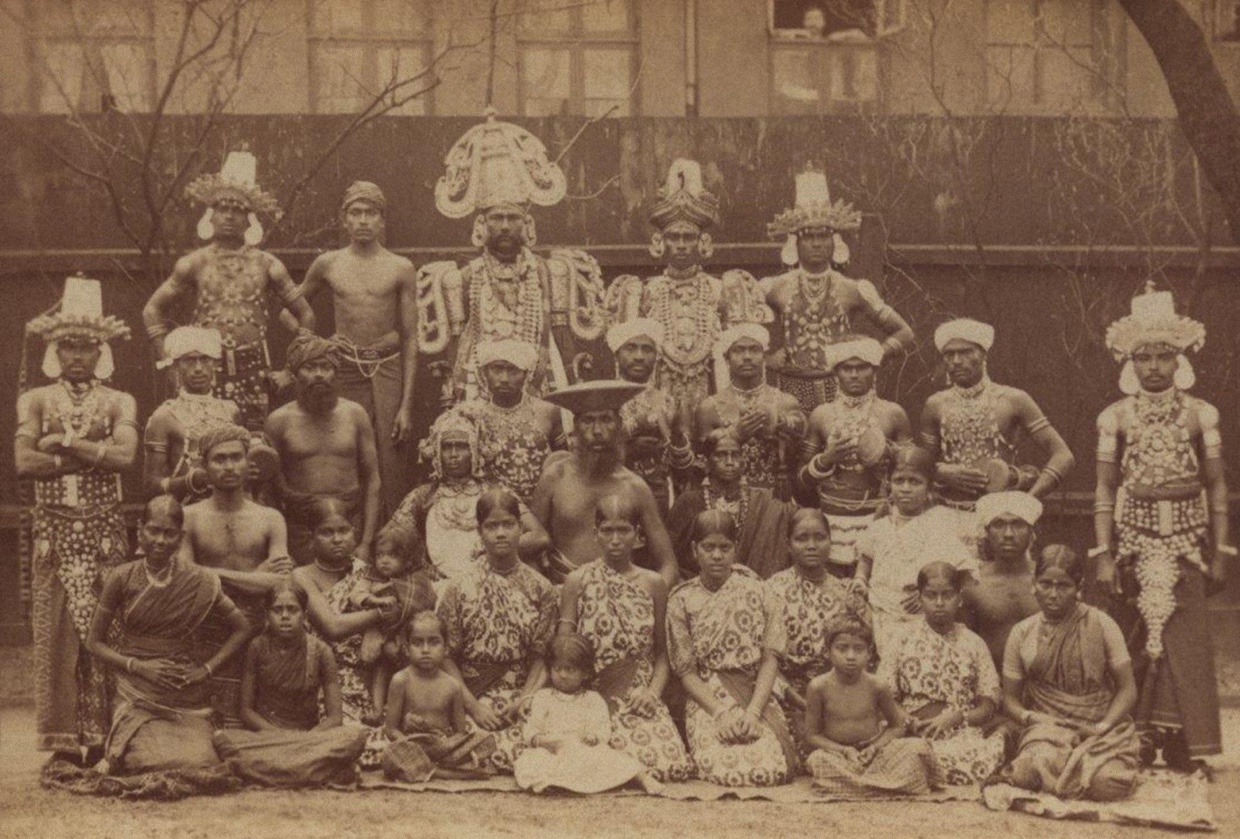

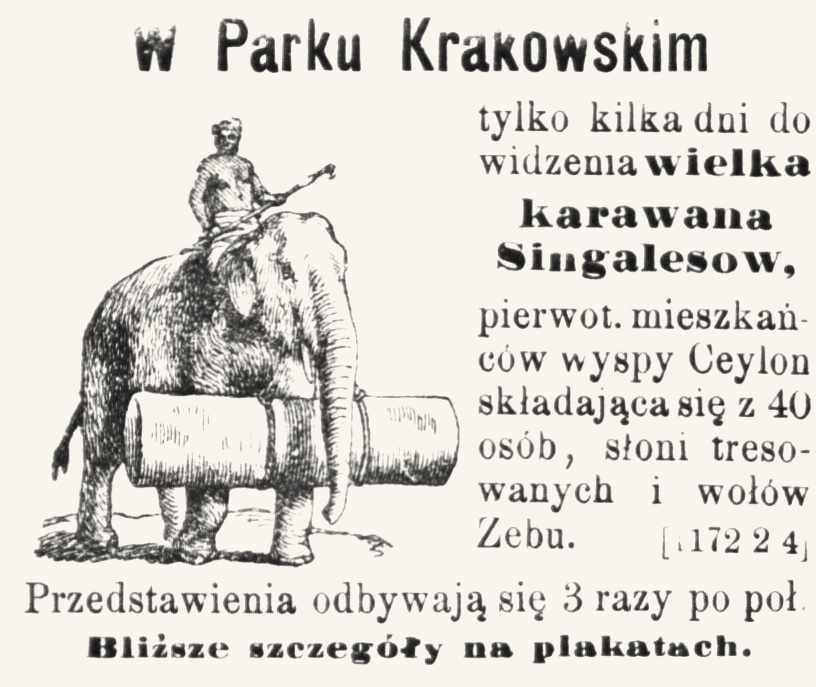

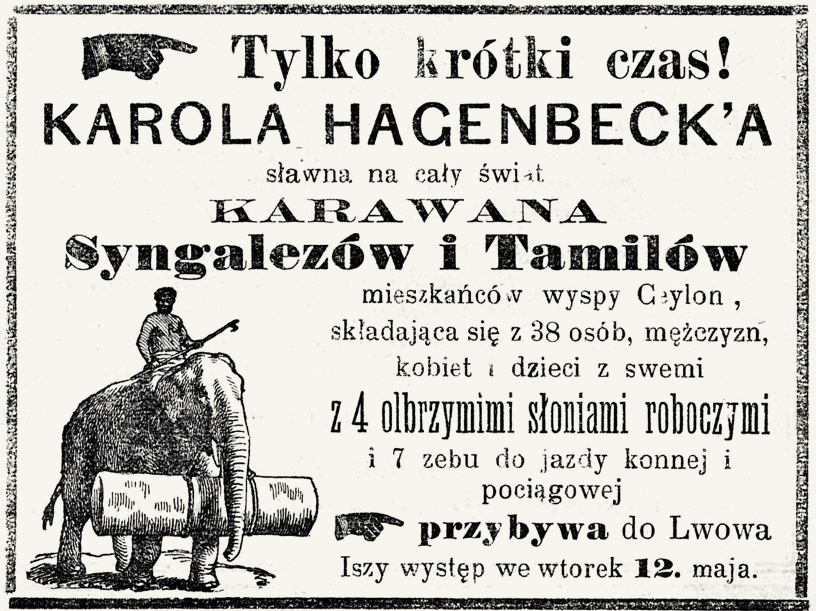

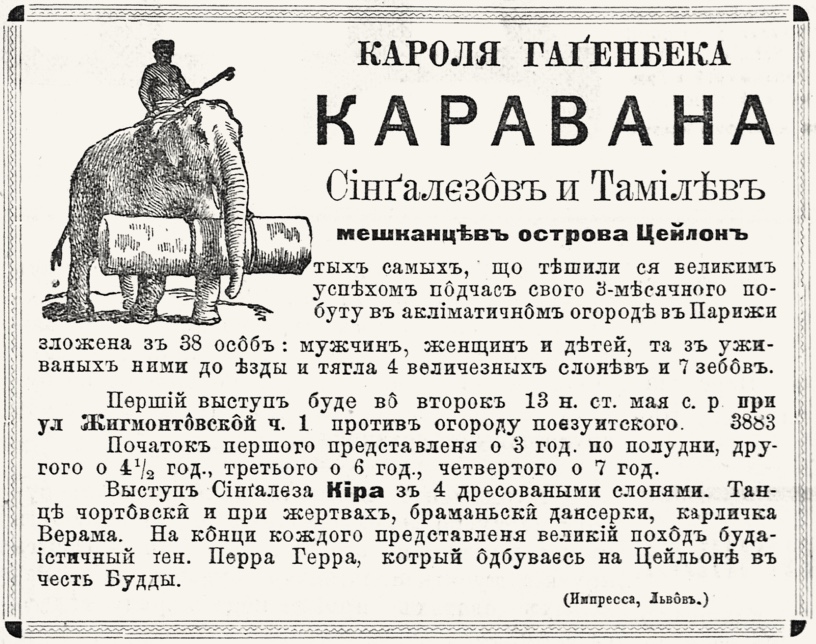

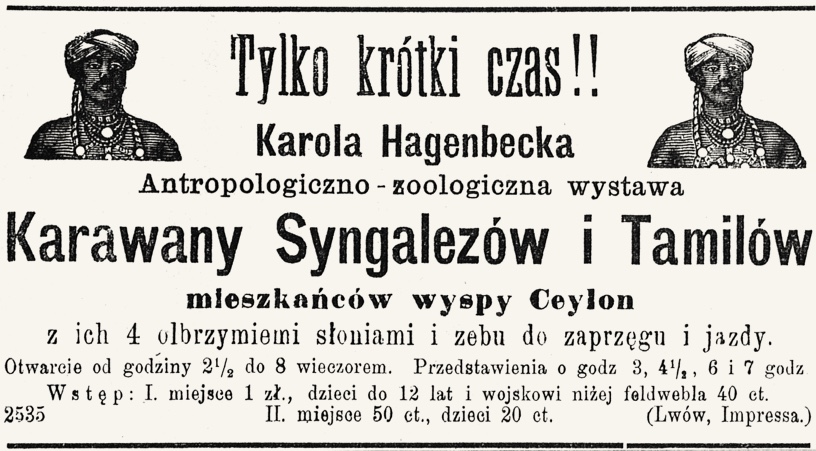

In May 1891, John Hagenbeck (in the press from Eastern European Galicia Karol, the name of the father, was used) arrived in Kraków with a group of several dozen (advertisements published in Kraków mentioned 40 members, the ones from Lviv 38) inhabitants of Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka). Their stay in Lviv was one of the many stops in the 1891 tour. As opposed to earlier itineraries (in 1888 and 1889), most of the locations visited lay under Habsburg rule, i.e. in Austria and Eastern European Galicia. Having left Lviv, the caravan headed for Odessa. The Lviv press advertised the shows—held between May 12 and May 24 at a venue in Zygmuntowska Street (presently Gogola Street), opposite the Jesuit Garden (presently Ivan Franko Park)—as a “caravan of the Sinhalese and the Tamil”. In Kraków, where the Ceylonese troupe performed from May 1 (in the Kraków Park), the local press mentioned only “a caravan of the Sinhalese”. Since the makeup of the group remained unchanged, it may be surmised that Hagenbeck simply wished to make his offer more attractive and elicit more interest from the local public (which translated into monetary profit). The array of attractions, which included not only dances, trained elephants and the great Perra Herra procession, but also performances by a female Sinhalese dwarf, points to the carnival-like nature of the late Hagenbeckian shows. The names of some troupe members, for example Veruma (the female dwarf) or Kiro, were also mentioned in previous Sinhalese tours of Europe. Reports by Lviv’s journalists indicate that the shows were very popular among the local public, as were performances of trained animals, especially elephants, which caused particular excitement. Although tickets for the shows were sold by a Lviv-based entrepreneur, postcards and programs of the performances could be purchased from members of the caravan. A unique postcard (in terms of the photographic depiction) bought during the Sinhalese troupe’s stay in Lviv was found in the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Kraków during research on the Staged Otherness… project. It bears the following handwritten caption: “(:pronounce: Symglz —[crossed out] Tamil:) A Caravan of Sinhalese and Tamils of Ceylon Island—taken around Europe by Karol Hagenbeck of Hamburg. Lvov 24/5 91”.

Advertisements for the “Sinhalese and Tamil Karawane”, published by the Polish- and Ukrainian-language press in Lviv, May 1891. Sources: Kurier Lwowski, May 9, 1891. Dilo, May 7, 1891.

Sources: Kurier Lwowski, May 12, 1891. Dilo, May 11, 1891.

Analysis of the promotional material for Hagenbeck’s 1891 show found in the Galician press demonstrates how much effort went into its advertising. Performances organised by his company were promoted in most of the more popular press titles in any given city, with the first advertisements appearing several days before the arrival of the non-European troupe, and continuing every day for the entire duration of the stay. In an attempt to reach the broadest spectrum of audience possible, Hagenbeck sponsored the printing of advertisements in several languages. The wording remained the same, as did the graphic design of the press advertisements (and most probably also the posters put up around the city); although at least several different designs existed, they all followed a certain model. The most popular image, which depicts a Sinhalese riding an elephant that is lifting a log with its trunk, was designed by the lithographer Adolph Friedlander, and used for the first time to promote the Sinhalese tour in 1885–86.

A Neger Karawane from the Nile Valley in Lviv, July–August 1893. Source: Ethnographic Museum in Kraków.

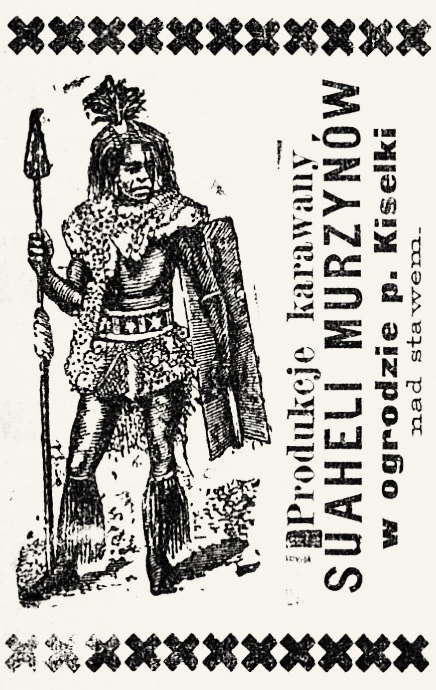

Advertisements from the Polish-language press in Lviv promoting the performances of an African troupe. The same graphic motif appears in German-language press in Gdańsk and in Slovenian-language press in Ljubljana. Source: Kurier Lwowski, July 30 and August 3, 1893.

Late in July 1893 Lviv was visited by a troupe of twenty African performers managed by the impresario Marton Fenyez. The exact route these non-European Others took through Central and Eastern Europe in 1893 remains unknown, yet it has been determined that they performed in Poznań between June 4 and 6. Having left Lviv, they headed for Gdańsk, where their shows were staged between August 31 and September 11. In Lviv, performances of these “black-skins” (Kurier Lwowski, August 4, 1893) were organised in two venues located in different parts of the city. In late July and early August (the caravan was initially scheduled to stay in Lviv until August 9), the troupe performed daily between 5 and 11 PM, by the pond in Kisielka Garden. The leisure garden, then a part of the Kisielka family estate, was situated in the vicinity of the oldest medicinal baths in Lviv. The scant accounts in the local press indicate that the African troupe performed war dances, songs and games, which were all recommended to the Lviv public as “an engaging and worthwhile form of entertainment”, especially “in the silly season, which offers no [other] diversions” (Kurier Lwowski, August 4, 1893). While the reasons for prolonging the troupe’s stay in Lviv are impossible to establish, it is certain that the foreign visitors remained in the city at least until August 18. Their performances were moved from the Kisielka Garden (most likely as the contract with the local entrepreneur expired) to a venue in Zygmuntowska Street, which had hosted the shows of the Sinhalese and Tamil caravan just two years before. Although the press offers very little information on the shows of the African performers, their stay at the Kisielka Garden is additionally corroborated by the postcard discovered in the collection of the Ethnographic Museum in Kraków, during the Staged Otherness… research project. The image it depicted was made by a Hungarian studio of photography called Blődy Arnold; the postcard itself was issued in Vienna. The history of this little piece of material evidence is as intriguing as it is mysterious. The postcard was probably brought to Lviv by members of the African troupe, who made additional profit from selling such souvenirs to the audience. The handwritten captions on the postcard indicate that it was purchased by one of the spectators during the troupe’s stay at the Kisielka Garden. It is unclear how the item ended up in Kraków. The anonymous author’s description added to the postcard is also interesting, as it contains information on the people depicted. They were marked with lowercase letters “a” to “f”. The image is captioned: “The caravan of Negros from Africa by the source of the Nile performed in Lviv in late July and early August 1893 in the garden by the Kisielka pond, a. chief, b. his first wife Alina (he has 4, and between 1 and 4 children by each of them), he is 28, his first wife 22, they have been together for 11 years, c. (woman), d. man playing harp, married couple, musicians, f. the heaviest and ugliest Negro with protruding [illegible] lips, e. his wife”. While the veracity of this information is difficult to ascertain, the description provided by the anonymous spectator triggered a process of transformation from ideal anthropological types to actual people.

“American Sham”. Buffalo Bill Wild West in the Kraków Błonia. Source: Nowości Ilustrowane, August 11, 1906.

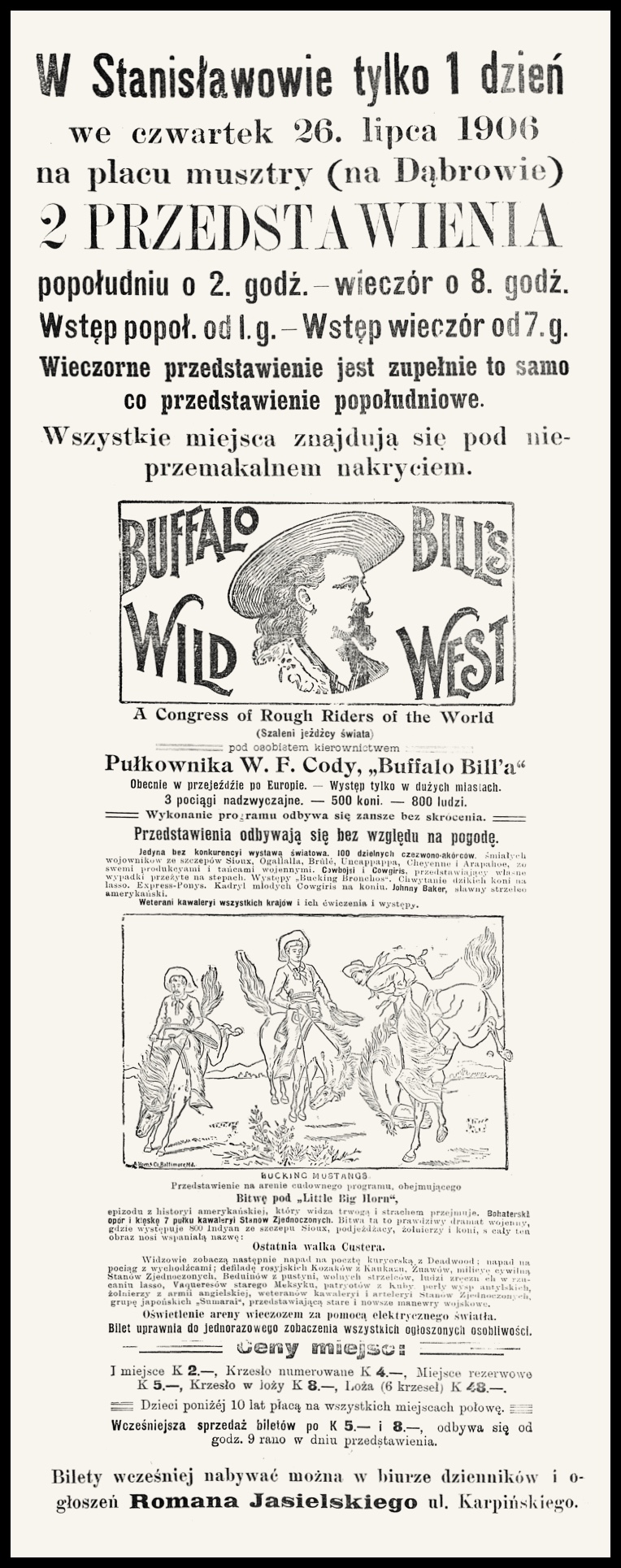

Advertisement promoting the Buffalo Bill shows in Stanisławów (today’s Ivano-Frankivsk) in 1906. Source: Kurier Stanisławowski, July 22, 1906.

On July 26, 1906, William Frederick Cody, also known as Buffalo Bill, gave two Wild West Show performances in Stanisławów. His troupe left for Tarnów that same evening. Stanisławów was one of the many towns in Eastern European Galicia visited by Buffalo Bill during his second tour of continental Europe (1902–6). Aside from what the local audience considered the main attraction, i.e. the opportunity to see ‘real Indians’ with their own eyes, Cody’s shows included performances by Cossacks, Mexicans, Bedouins, Cubans and the Japanese. In practice, the Wild West Show represented the next stage in the evolution of the phenomenon of ethnographic shows: it resembled circus programs involving performances by non-European Others. In many Polish-language periodicals published in cities such as Kraków or Lviv, the arrival of Buffalo Bill’s show was used by conservative circles to draw attention to current social issues, and—less directly—to cricitise the Habsburg authorities. This being said, the Wild West Show enjoyed much popularity wherever it went. The audience was impressed with the scale of the enterprise and its technical and organisational efficiency. What residents of Stanisławów found important was that the shows staged in the Dąbrowa district were in no way different from those presented earlier in Paris and other metropolises of Europe. In practice, Buffalo Bill’s performances in Stanisławów allowed the local residents to participate in a certain community of culture and share the experiences that shaped this community.

![]()

Credits:

Dagnosław Demski, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences; Dominika Czarnecka, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences