ETHNOGRAPHIC SPECTACLES IN CZECH LANDS

Soon after the railways connected the inland parts of the continent to the North and the Adriatic Sea, Czech lands appeared on the maps of Carl Hagenbeck and other entrepreneurs with the words “exotic”. Since 1870s, the growing industrial hubs of Prague/Prag, Brno/Brünn, Opava/Troppau and Liberec/Reichenberg had become usual stops for ethnic shows travelling the Habsburg monarchy. Carl Hagenbeck and his company catered to local audiences with shows bringing “natives” from different parts of the world. In 1880 Prague hosted Hagenbeck’s Labrador Inuit troupe featuring Abraham Ulrikab (1845–1881), who described his travels through the “land of the Catholics” in his private diary. Shows that presented peoples from the “Far North” such as the Samoyed people (1882), and later from the Indian subcontinent (Ceylon exhibition 1885), were later replaced by shows on the peoples of Africa, particularly Dahomey (1892, 1898) and Ashanti (1897, 1899) from today’s Benin and Nigeria. Silesian and Moravian cities also witnessed the famous Buffalo Bill’s (William Cody) “Wild West Show” in 1906. The activities of Hagenbeck and his associates also inspired local actors. Czech-Austrian traveller Emil Holub (1847–1902) emulated the form of the ethnographic shows for his African Exhibition, presented in Vienna (1891) and Prague (1892). On a much smaller scale, various local actors staged mock-shows with black-face performers acting as Africans. Thus, by the end of the nineteenth century, public space in the Czech lands had been decisively permeated by racial and colonial imagery.

Locating Prague on the colonial map of the World through the 1908 Industrial Exhibition. Source: Pražský illustrovaný kurýr, June 8, 1908, title page.

Presentations of exoticised people fed into two complimentary narratives: the theory of evolution and the idea of Western dominance. These two ideas had been most persuasively cobbled together via the medium of industrial exhibitions at which “native villages” stood as the counterpoint to the industrial progress of Europe. The presence of the ‘exotic’ performers at the 1908 exhibition in Prague helped to sustain the idea of Czechs as a developed industrial nation. At the same time the confrontation with Africans or people from Asia allegedly testified to the worldliness of Prague and its belonging to Western civilisation. The same dynamics was to be observed in the case of the Czech-German exhibition Liberec/Reichenberg 1906.

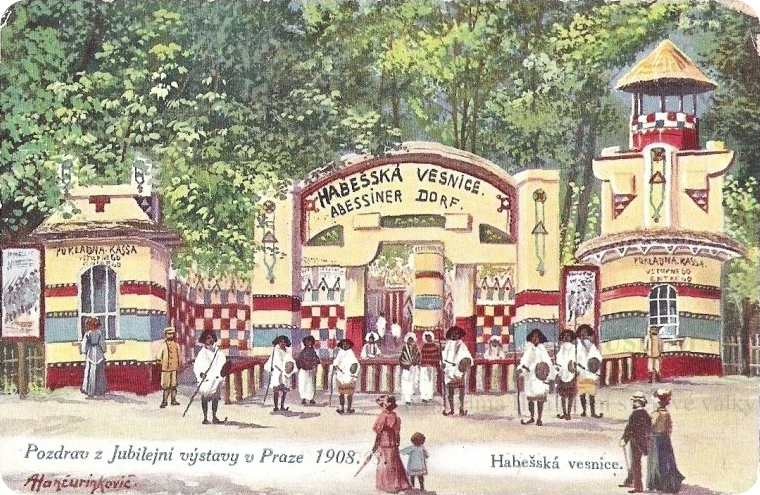

Entrance to the “Abessiner village” at the Industrial Exhibition Prague, 1908. Picture postcard. Source: Radauer Collection.

In the wake of the scramble for Africa, ethnographic shows from that part of the world started to dominate the scene in the Czech lands and elsewhere. The “Abessiner village” with fifty performers presented by Emanuel Porfi at the 1908 Prague Industry Exhibition belonged to the biggest of such events in Prague. Similar to other African groups, the popularity of Abbesiner coincided with the wars waged in respective parts of the continent by colonial powers, Italian interventions in Abyssinia (Ethiopia) being the case in point here. The audience in Prague read the performance as a confirmation of Western dominance in the world. Local media focused on the otherness of the Abessiner, specifically on their pigmentation and other bodily features that were described and interpreted through the language of race. A central motif that reappeared in the local responses to the exhibition was the supposed primitive sexuality of the othered bodies. Commentaries on the special attractivity of the Abbesiner to local women resonated with panic over morality and the purity of the national body supposedly threatened by emancipation, respectively by contacts with ‘different races’.

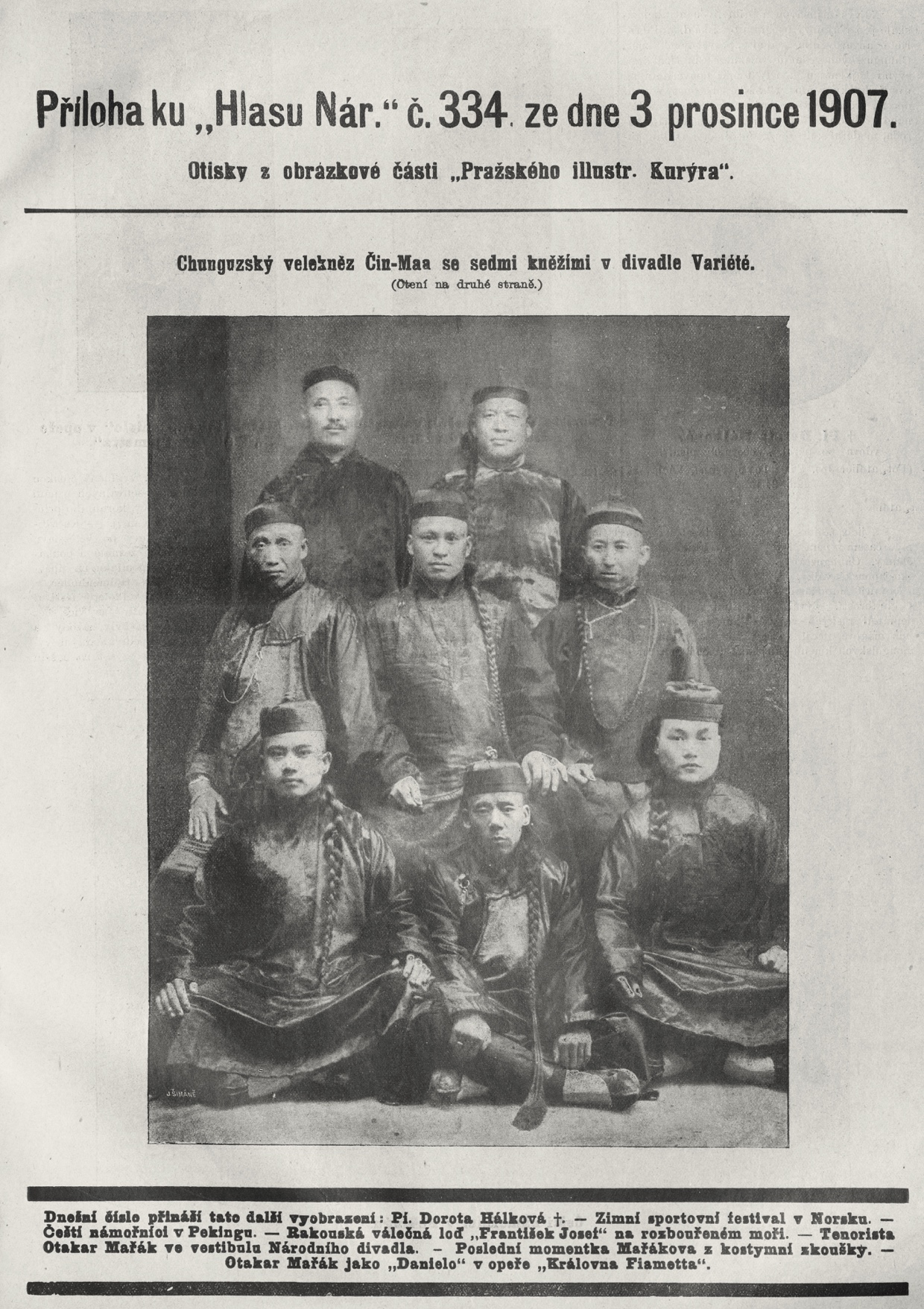

A group of seven individuals billed and presented as “Seven holy Tungus” performed in Prague’s theatre Varieté around Christmas of 1907. The origin and individual stories of these performers is unknown. They were presented mainly as acrobats and illusionists, however the local media also commented on the involvement of the Tungus people in the colonial conflicts of the time, the Boxer Uprising (1899–1901) and the war for Manchuria (1904–1905). Generally, unlike Africans on one hand, and American ‘Indians’ on the other, Asian populations were imagined as ‘oriental enemies’ to Western domination of the world. The Czech media emulated the ‘yellow peril’ narrative. Together with the Tungus advertisements, local press issued images of Czech soldiers who were serving as part of the allied occupation contingent in China. The Tungus performance thus symbolically put Prague on the colonial map of the world reaffirming that the city and its inhabitants belong to the colonial metropolis.

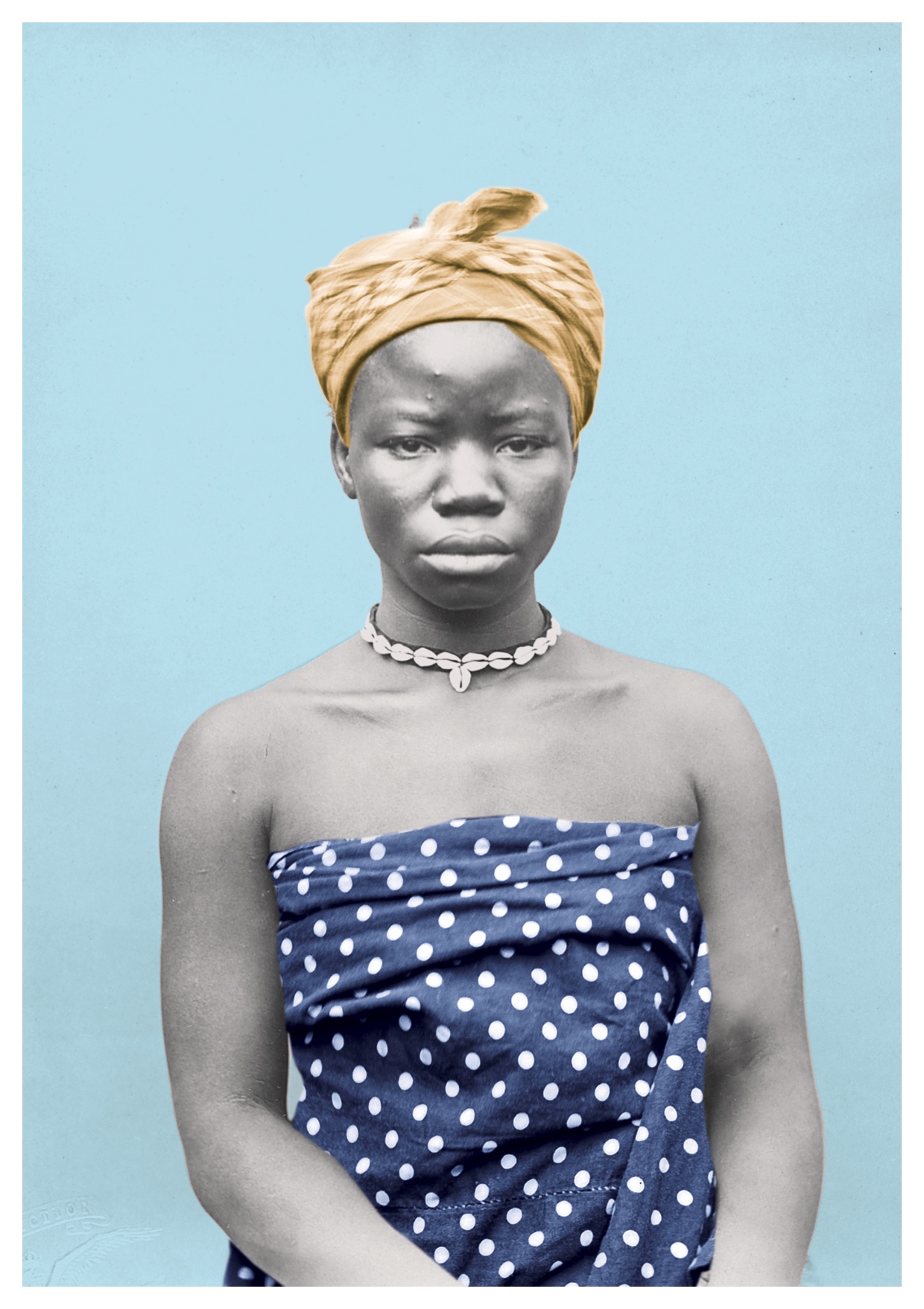

Gutta (also spelled Guthu in German, Goutto/Gouthout in French), around 1858-1892. Source: Musée du quai Branly (picture modified by Ludomir Franczak).

Gutta was born near Abeokouta (today’s Nigeria) among the Egba, a subgroup of the Yoruba people. At the age of twenty-two Gutta made her way to Europe, arriving on the cargo ship the Winnebah owned by the African Steamship Co., from Porto Novo, via England, to Hamburg where she arrived in the autumn of 1890. From there she found her way to the “Amazons of Dahomey” group, led by impresario John Hood who was associated to Carl Hagenbeck’s network of companies. “Amazons of Dahomey” were men and women from the Yoruba and Ashanti peoples who played the roles of Dahomean warriors for European audiences. Their impresarios capitalised on the general interest in “unruly African savages”, particularly after the first Franco-Dahomean war (1890). The cast probably learned their weapon skills in Hamburg, where they also sewed the costumes for the entire group, which initially consisted of about five men and nine women and later grew to a size of about thirty-five people. The group toured today’s Germany, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Poland, Austria, Hungary and Czech Republic. In September 1892, the group arrived in Prague, where Gutta contracted pneumonia or typhoid fever, and died after a few days. Her solemn funeral was a big spectacle that took place on September 21. She was buried in the central Prague cemetery. Two years later, her remains were excavated by anthropologist Jindřich Matiegka and placed in the university collection, from where they found their way to the Museum of Man (Hrdličkovo museum člověka). Being still on the exhibit, the remains of Gutta presents an important part of the local colonial heritage and a challenge for the local institutions to come to terms with their complicated histories.

Photography of A.V. Frič and Cerwuis. Source: National Museum of the Czech Republic – Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures, Prague

Piosad Mendoza Cerwuis, a member of the Ishiro (Spanish: Chamacoco) community from Pacheco settlement located on the riverbanks of Paraguay, Grand Chaco was undoubtedly one of the best known ‘natives’ to visit early-20th-century Prague. The life-story of Čerwuiš reverberated and fed into the East and Central European fascination with American ‘Indians’. The narrative of the noble savage trumped by merciless civilisation resonated with the anti-imperialist sentiments and protests against national discrimination within Austria-Hungary. Such reasoning may have eventually led to unexpected encounters, such as that one between Čerwuiš and the Czech traveller Alberto Vojtěch Frič (1882–1944) who brought the Ishiro individual to Prague in 1908. The official story told about the encounter says that Frič invited Čerwuiš to come to Europe to search for a cure that would help save his people from an infectious disease. Yet, it is evident that Frič also brought Čerwuiš as an exotic specimen that would bring more attention to his public activities and help create his self-image as a traveller-adventurer. The story of Čerwuiš continues to animate local discussions today in the form of books, comics and theatre plays. In 2004 the relatives of Frič started the Checomacoco developmental aid project in the Puerto Esperanza community, which builds upon the founding story of Čerwuiš and activities of the Czech traveller around the River Paraguay.

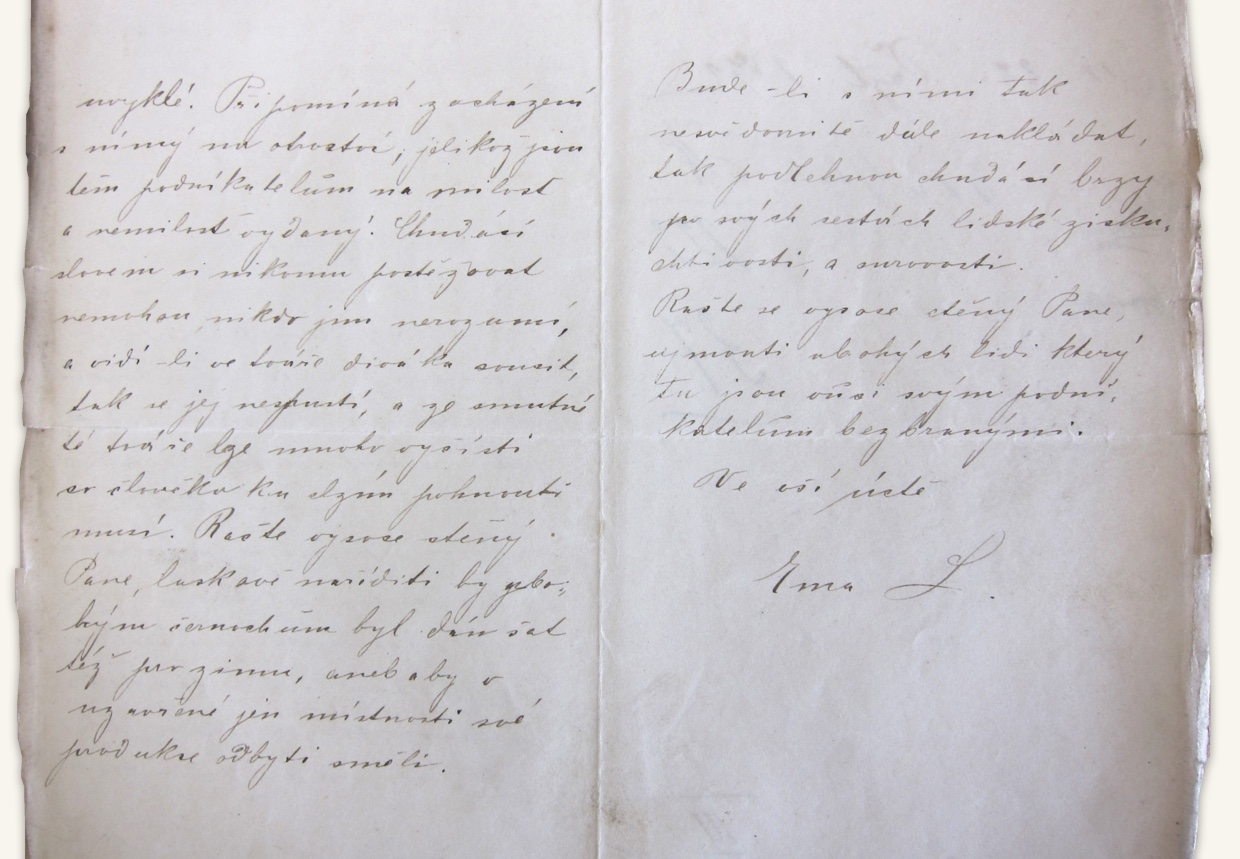

Addressed to the Police Directorate in Prague, September 9, 1892. Source: National Archive of the Czech Rep., Police Directory Prague I – general registry 1891-1895, box 3687, sig. H 122/37 John Hood

Following excerpt from the sources demonstrates, that the ethnographic shows did not only evoked fascination but also mounted criticism among the local audiences. Here, a visitor named Ema L. complains about the exploitative nature of such enterprises.

“I’ve been visiting the exhibition of Dahomeans at the Střelecký island these days to find out that the poor people aren’t allowed to wear any clothes. They were bare-footed, they trembled with cold and it was indeed a terrible look at the poor negroes (černochy) exploited by their merciless impresario. Although they are accustomed to a warm climate, he does not give them any clothes even after their show when they are all swept. Such treatment is a blunt slavery, because these people are defenceless against their impresarios. Poor people, nobody hears their complaints. Only when they see a compassionate face in the audience they stare into it, and their sad expression turns one automatically to cry. … If they continue to be treated like this, they will soon all become victims of human greed and coarseness”.

Ema L.

![]()

Credits:

Filip Herza, Institute of Ethnology, Czech Academy of Sciences; Ludomir Franczak (Gutta); Markéta Křížová, Charles University Prague (Čerwuiš)