METROPOLITAN IMPERIAL ENTERPRISE IN VIENNA AND BUDAPEST

Ethnographic shows were formerly often linked specifically to countries with colonial histories. However, they were also widespread in Central and Eastern Europe where most countries did not have colonies abroad. Starting in the 1870s the first groups started performing in Vienna and Budapest—the two capitals of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—and continued until after the Great War. Although most shows performed in the capitals, some groups also toured smaller cities and villages if it seemed economically promising. One of the most successful ethnic groups to perform in Vienna were the Ashanti people from today’s Ghana. In 1896 the first group of Ashanti from the ‘Gold Coast’ came to Vienna by boat after having performed at the Allatkert (zoo) in Budapest. Their performances at the Thiergarten am Schüttel—a private zoo in the second district of Vienna—were so well received that groups from the same region returned in 1897 and 1899. Their popularity was so large that social events such as balls, gymnastic festivals, a theatre play and a book by Peter Altenberg were Ashanti themed. Even a lost painting by Gustav Klimt is thought to be a portrait of one of the members of an Ashanti group. At least fifty groups performed in the Austro-Hungarian Empire over a period of roughly forty years. In Vienna many groups performed before the Rotunda built for the Vienna World’s Fair in 1873, at the Thiergarten am Schüttel or at venues in the Prater such as Venedig in Wien (Venice in Vienna), one of the first amusement parks in the world. The two main venues for ethnographic shows in Budapest were the Allatkert (zoo) and the Angol Park (an amusement park). Although very popular for many years, the craze for this type of racist stereotypical entertainment seems to have ended in the years following the Great War, with the last large groups touring in the mid-1920s. Even though mainly forgotten the phenomenon of ethnographic shows certainly influenced the way people in Austria and Hungary perceived ethnic groups from outside Europe at the time, with some stereotypes from the period lasting potentially until today.

The Dahomey Caravan, 1892. Source: Collection Radauer.

The cabinet card of a group of “Dahomey Warriors” who performed, among others, at the Budapest Zoo while touring through most of Europe for several years. The group size and the specific participants seem to have changed several times throughout the years. Due to the Dahomean Wars of the 1890s the myths of the legendary female fighters of Dahomey were well known among Europeans, leading to a large interest in groups from this region.

Hagenbecks’ Malabar people in Hamburg, around 1900. Source: Collection Radauer.

Carl Hagenbeck’s name was one of the most important in the context of the ethnographic show and many groups toured under his management, such as this group from Ceylon (today’s Sri Lanka). Thanks to his many years of experience importing animals from all over the world for Western zoos, Hagenbeck had a great network in many countries that facilitated the recruitment and organisation of ethnographic exhibitions.

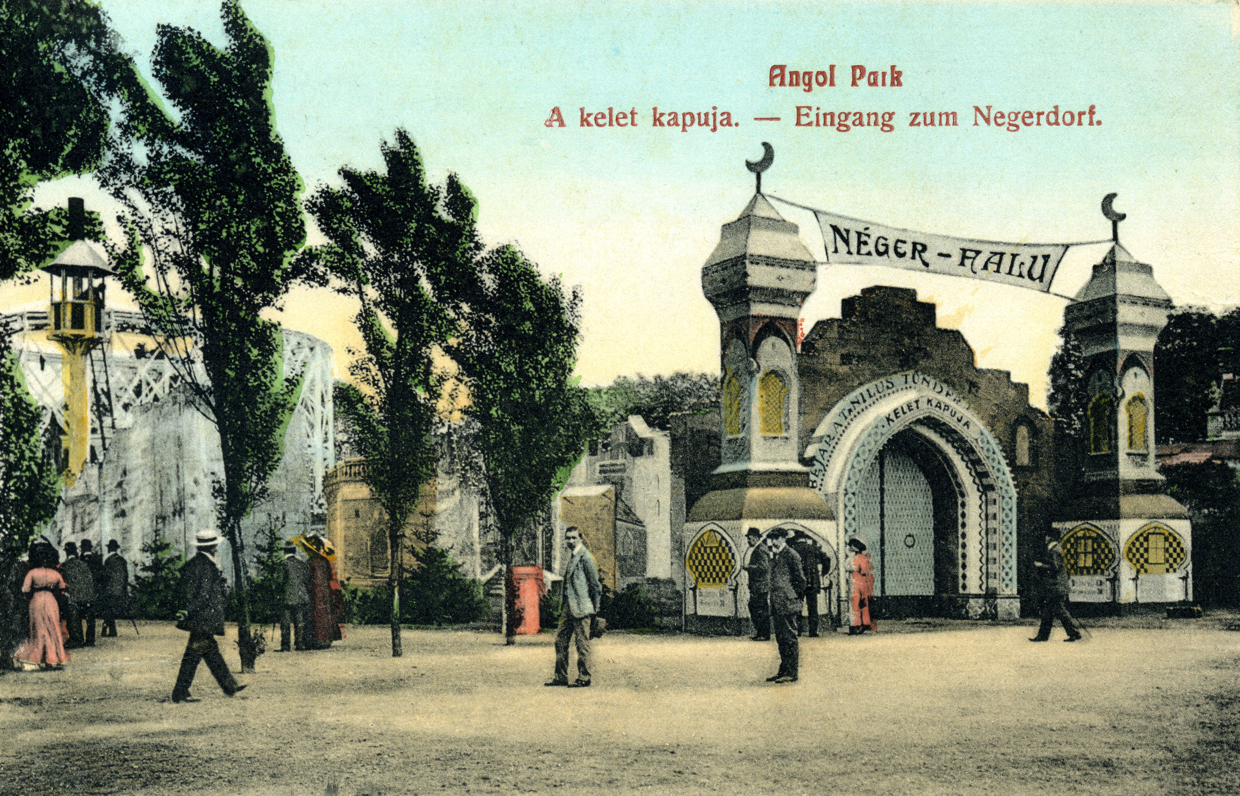

1912 (postcard) of the main entrance to the “African village” (Néger Falu) at Angol Park in Budapest. Source: Collection Radauer.

As in many European cities, zoos were a very popular venue for ethnographic shows due to their ideal infrastructure: well connected by public transport, enough space for the performances and facilities to house the animals that often accompanied the groups. In addition, zoos were known to the public as place of entertainment and education.

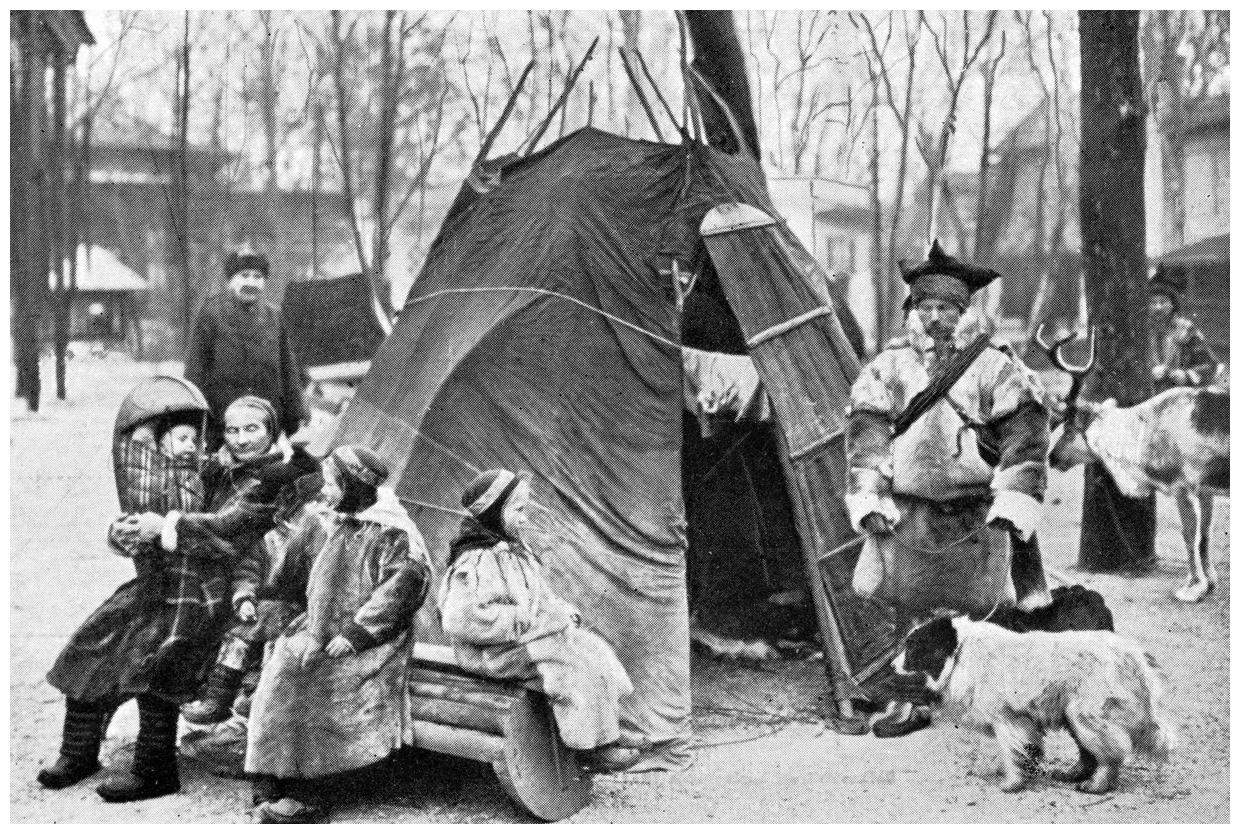

1913 (postcard) of a group of Sami (lappföldiek) at Budapest Zoo. Source: Collection Radauer.

Undated advertisement for the Viennese Thiergarten am Schüttel, a former private zoo close to today’s Prater, that mentions ethnographic shows (ethnographische Schaustellungen) as one of their attractions. In order to attract more visitors, zoos included ethnographic shows in their regular programs, often even adapting and dedicating specific areas to these shows. Source: Collection Radauer.

1889 cabinet card by M. Reichstein, Vienna of the so-called Jangaui-Karawane, a small group of four men and a woman. They were advertised as being from Central Africa and toured through Austria’s cities such as Linz, were this card was bought. Source: Collection Radauer.

1892 cabinet card by Liatti & Partein, Graz of the Suaheli-Karawane, which supposedly came from Kap Delgado in then German East Africa, today’s Mozambique. Source: Collection Radauer.

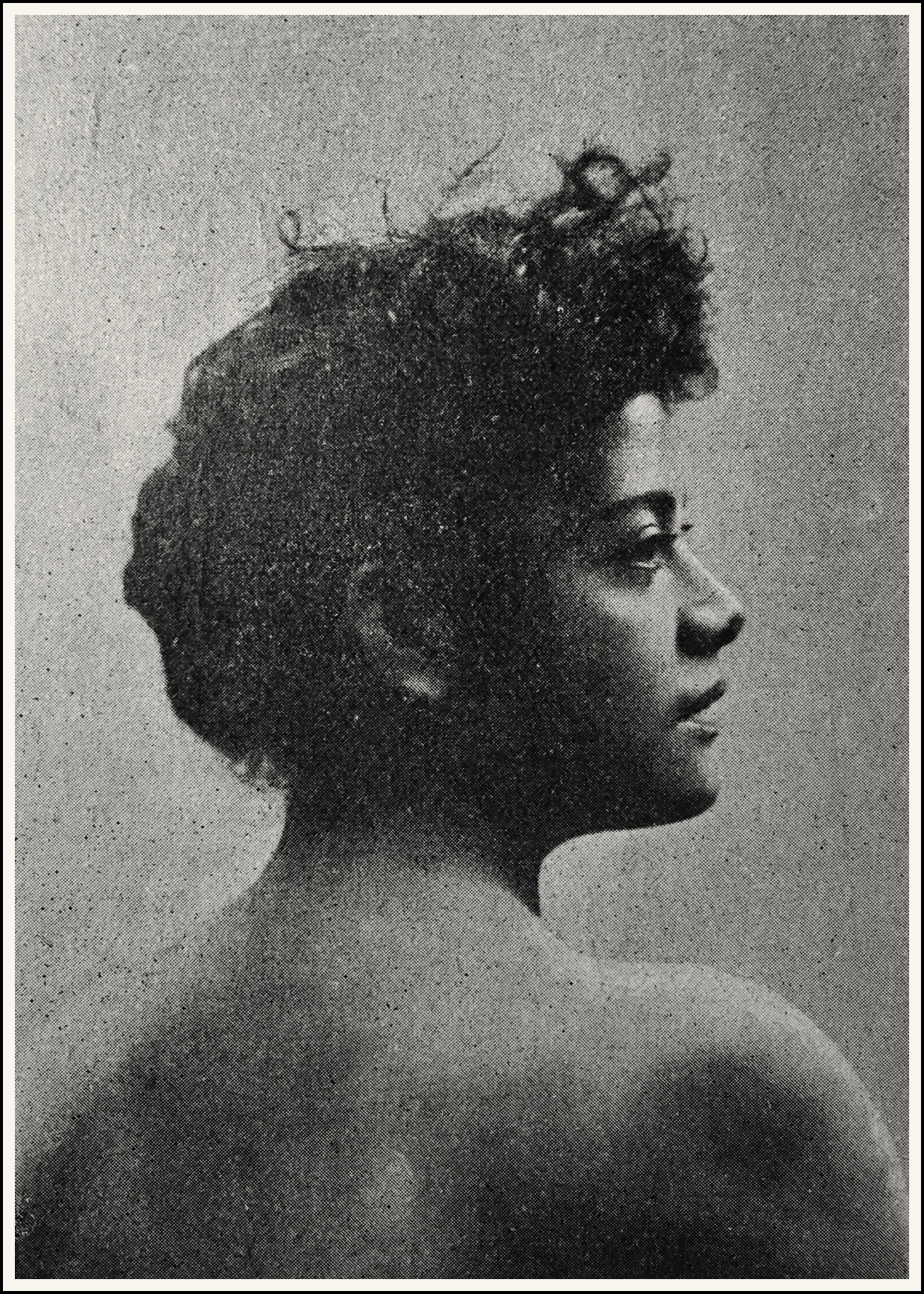

Newspaper illustration from Wiener Bilder, June 6, 1897. Source: Collection Radauer.

Newspaper illustration showing one of the members of the Samoan group organised by the brothers Marquardt. The image depicts Fai, who was often called Princess Fai because of her appealing looks to the European eye. This caused several arguments within the Samoans since Fai’s social rank was lower than other group members.

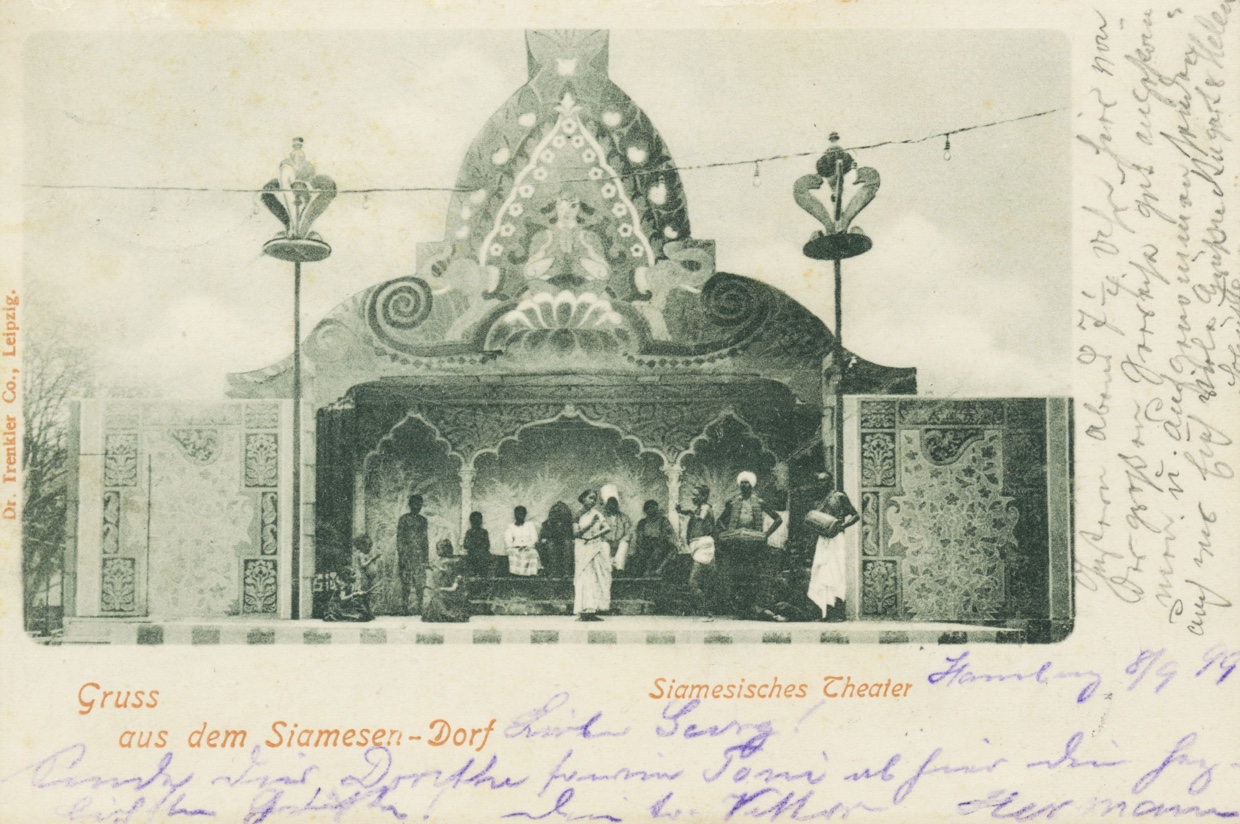

Postcard of the Siamese-Dorf (Siamese village) in Vienna, 1899. Source: Collection Radauer.

The postcard shows the stage, called the Siamese theatre, where dance and other performances were staged several times per day. The advertisements for ethnographic shows often included timetables for all specific performances, so visitors knew exactly when they could witness which part of the show.

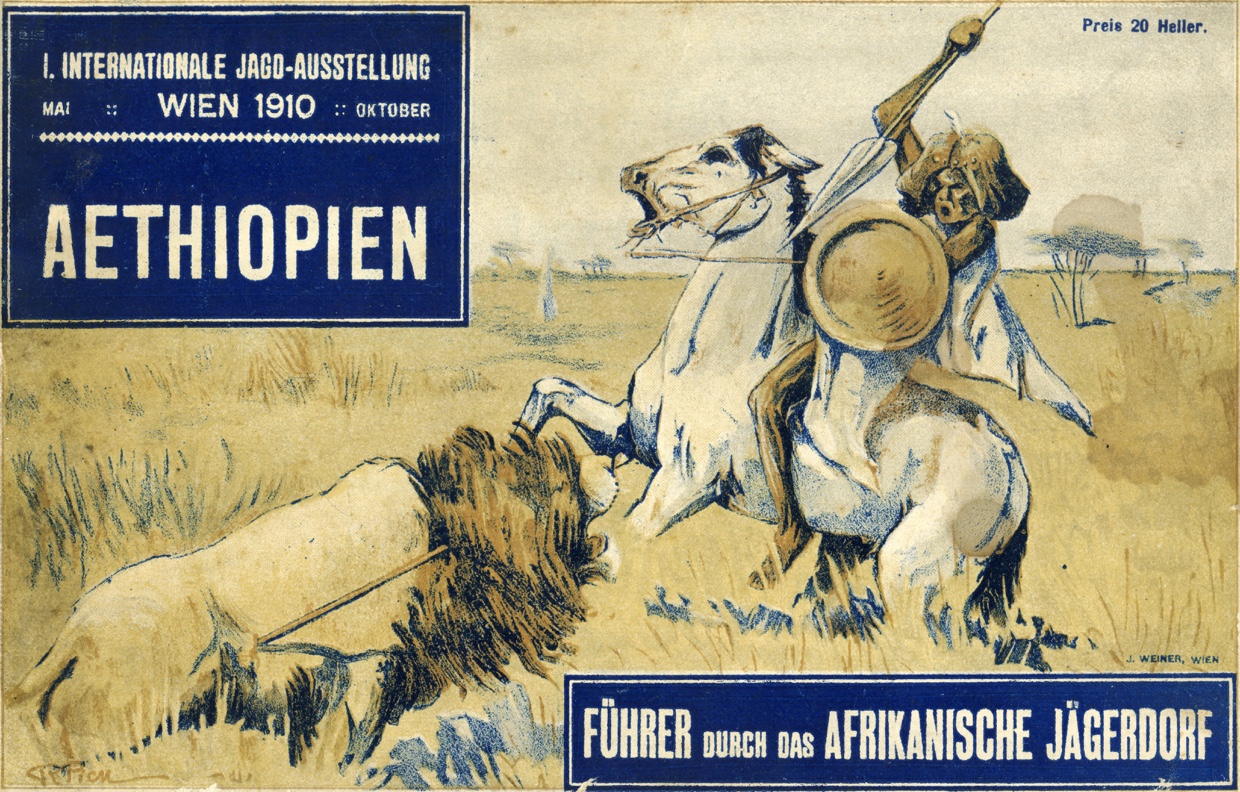

The front page of a booklet describing the International Hunting Exhibition in Vienna, 1910. Source: Collection Radauer.

The International Hunting Exhibition in Vienna in 1910 also contained the Afrikanische Jägerdorf (African hunting village) as a part of the amusement park. The group from eastern Africa, which toured Europe continuously for a few years, performed scenes of daily life in Abyssinia for the Viennese audience.